INSTRUCTIONS AND PROPHECIES OF THE Blessed MOTHER ALIPIA GOLOSEEVSKY, Kyiv...

Anaximander (c. 610 - after 547 BC), an ancient Greek philosopher, a representative of the Milesian school, the author of the first philosophical work in Greek, On Nature. A student of Thales. Created a geocentric model of the cosmos, the first geographical map. He expressed the idea of the origin of man "from an animal of another species" (fish).

Anaximander (Greek) - mathematician and philosopher, son of Praxiad, b. in Miletus 611, died 546 BC. Among all the Greek thinkers of the most ancient period, the Ionian natural philosophers, he embodied in the purest form their speculative desire to know the origin and beginning of all things. But meanwhile, while other Ionians recognized one or another physical element, water, air, etc., as such a beginning, A. taught that the initial basis of all being is the boundless (toapeiron, infinite), the eternal movement of which singled out the primary opposites of heat and cold , dryness and moisture and to which everything returns again. Creation is the decomposition of the infinite. According to him, this infinite constantly separates from itself and constantly perceives certain, unchanging elements, so that the parts of the whole change forever, while the whole remains unchanged. With this transition from the certainty of the material explanation of things to an abstract representation, A. emerges from the ranks of the Ionian natural philosophers. See Seidel, "Der Fortschritt der Metaphysik unter den altestenjon. Philosophen", (Leipzig, 1861). How he actually used his hypothesis to explain the origin of individual things, there is only fragmentary information about this. Cold, combined with moisture and dryness, formed the earth, having the shape of a cylinder, the base of which is related to height as 3:1, and occupying the center of the universe. The sun is in the highest celestial sphere, more land 28 times and represents a hollow cylinder from which fiery streams pour; when the hole closes, an eclipse occurs. The moon is also a cylinder and 19 times the size of the earth; when tilted, it is obtained lunar phases, and the eclipse occurs when it completely turns over. A. first in Greece pointed to the inclination of the ecliptic and invented a sundial, with which he determined the equinoxes and solar rotations. He is also credited with compiling the first geographical map of Greece and making the celestial globe, which he used to explain his system of the universe. See Schleiermacher, "Uber A.", (Berl., 1815). For the close connection of his cosmogony with Eastern speculations, see Busgen, "Uber das apeiron des A.", (Wiesbad., 1867). P. G. Redkina, "From lectures on the history of the philosophy of law."

We know almost nothing about his life. Anaximander is the author of the first philosophical work written in prose, which laid the foundation for many works of the same name by the first ancient Greek philosophers. Anaximander's work was called "Peri fuseos", that is, "On Nature." Similar titles of works indicate that the first ancient Greek philosophers, unlike the ancient Chinese and ancient Indian ones, were primarily natural philosophers, physicists ( ancient authors called them physiologists). Anaximander wrote his work in the middle of the 6th century. BC. From this work, several phrases and one whole small fragment, a coherent fragment, have been preserved. The names of other scientific works of the Milesian philosopher are known - "Map of the Earth" and "Globe". The philosophical doctrine of Anaximander is known from doxography.

It was Anaximander who expanded the concept of the beginning of everything that exists to the concept of "arche", that is, to the beginning, substance, that which lies at the basis of everything that exists. The late doxographer Simplicius, separated from Anaximander by more than a millennium, reports that "Anaximander was the first to call that which lies at the basis the beginning." Anaximander found such a beginning in a certain apeiron. The same author reports that Anaximander's teaching was based on the proposition: "The beginning and foundation of all things is apeiron." Apeiron means "limitless, limitless, endless". Apeiron is the neuter gender of this adjective, it is something limitless, limitless, endless.

Anaximander. Fragment of Raphael's painting "The School of Athens", 1510-1511

It is not easy to explain what Anaximander's apeiron is material, material. Some ancient authors saw in apeiron "migma", i.e. a mixture (of earth, water, air and fire), others - "metaksyu", something between two elements - fire and air, others believed that apeiron is something indefinite . Aristotle thought that Anaximander came in his philosophical teachings to the idea of apeiron, believing that the infinity and infinity of any one element would lead to its preference over the other three as finite, and therefore its infinite Anaximander made indefinite, indifferent to all the elements. Simplicius finds two bases. As a genetic principle, apeiron must be limitless so as not to run out. As a substantial beginning, Anaximander's apeiron must be infinite, so that it could underlie the mutual transformation of the elements. If the elements turn into each other (and then they thought that earth, water, air and fire were capable of turning into each other), then this means that they have something in common, which in itself is neither fire, nor air, nor land or water. And this is the apeiron, but not so much spatially limitless as internally limitless, that is, indefinite.

In the philosophical teaching of Anaximander, apeiron is eternal. According to the surviving words of Anaximander, we know that apeiron "does not know old age", that he is "immortal and indestructible." He is in a state of perpetual activity and perpetual motion. Movement is inherent in apeiron as an inseparable property from it.

According to the teachings of Anaximander, apeiron is not only the substantial, but also the genetic beginning of the cosmos. From it not only everything essentially consists in its basis, but also everything arises. Anaximander's cosmogony is fundamentally different from the above cosmogony of Hesiod and the Orphics, which were theogony only with elements of cosmogony. Anaximander no longer has any elements of theogony. From theogony, only an attribute of divinity remained, but only because apeiron, like the gods of Greek mythology, is eternal and immortal.

Apeiron Anaximander makes everything out of himself. Being in a rotational motion, apeiron distinguishes from itself such opposites as wet and dry, cold and warm. Pair combinations of these main properties form earth (dry and cold), water (wet and cold), air (wet and hot), fire (dry and hot). Then in the center is collected as the heaviest earth, surrounded by water, air and fiery spheres. There is an interaction between water and fire, air and fire. Under the action of heavenly fire, part of the water evaporates, and the earth partially emerges from the oceans. This is how dry land is formed. The celestial sphere is torn into three rings surrounded by dense opaque air. These rings, says the philosophical teaching of Anaximander, are like the rim of a chariot wheel (we say: like a car tire). They are hollow inside and filled with fire. Being inside the opaque air, they are invisible from the ground. There are many holes in the lower rim through which the fire enclosed in it is visible. These are the stars. There is one hole in the middle rim. This is the moon. There is also one at the top. This is the Sun. From time to time, these openings are able to completely or partially close. This is how solar and lunar eclipses. The rims themselves revolve around the Earth. The holes move with them. This is how Anaximander explained the visible movements of the stars, the Moon, and the Sun. He was even looking for numerical relationships between the diameters of the three cosmic rims or rings.

This picture of the world given in the teachings of Anaximander is incorrect. But still striking in it is the complete absence of gods, divine forces, the courage of an attempt to explain the origin and structure of the world from internal causes and from a single material and material principle. Secondly, the break with the sensual picture of the world is important here. How the world appears to us and what it is are not the same thing. We see the stars, the Sun, the Moon, but we do not see the rims, the openings of which are the Sun, the Moon, and the stars. The world of the senses must be investigated, it is only a manifestation of the real world. Science must go beyond direct contemplation.

The ancient author Pseudo-Plutarch says: "Anaximander ... claimed that apeiron is the only cause of birth and death." The Christian theologian Augustine lamented Anaximander for having "left nothing to the divine mind."

The dialectics of Anaximander was expressed in the doctrine of the eternity of the movement of apeiron, the separation of opposites from it, the formation of four elements from opposites, and cosmogony - in the doctrine of the origin of the living from the inanimate, man from animals, i.e., in the general idea of the evolution of living nature.

Anaximander also belongs to the first deep conjecture about the origin of life. Living things originated on the border of the sea and land from silt under the influence of heavenly fire. The first living beings lived in the sea. Then some of them went to land and threw off their scales, becoming land. Man originated from animals. In general, all this is true. True, man, according to the teachings of Anaximander, did not originate from a land animal, but from a sea animal. Man was born and developed to an adult state inside some huge fish. Having been born as an adult (because as a child he could not have survived alone without parents), the first man went out onto land.

Eschatology (from the word "eschatos" - extreme, final, last) is the doctrine of the end of the world. In one of the surviving fragments of the teachings of Anaximander it is said: “From which the birth of everything that exists, everything disappears out of necessity. Everything receives retribution (from each other) for injustice and according to the order of time. The words "from each other" are in brackets because they are in some manuscripts and not in others. One way or another, from this fragment we can judge the form of Anaximander's work. According to the form of expression, this is not a physical, but a legal and ethical essay. The relationship between the things of the world is expressed in ethical terms.

This fragment of the teachings of Anaximander caused many different interpretations. What is the fault of things? What is retribution? Who is to blame for whom? Those who do not accept the expression "from each other" think that things are guilty before apeiron because they stand out from it. Every birth is a crime. Everything individual is guilty before the beginning for leaving it. The punishment is that the apeiron consumes all things at the end of the peace period. Those who accept the words "from each other" think that things are not guilty before apeiron, but before each other. Still others generally deny the emergence of things from apeiron. In the Greek quotation from Anaximander, the expression "from what" is in plural, and therefore under this “from what” apeiron cannot be meant, and things are born from each other. Such an interpretation contradicts Anaximander's cosmogony.

It is most likely to believe that things, arising from apeiron, are guilty before each other. Their fault lies not in their birth, but in the fact that they violate the measure, that they are aggressive. Violation of the measure is the destruction of the measure, the limits, which means the return of things to a state of immensity, their death in the immeasurable, that is, in the apeiron.

In the philosophy of Anaximander, the apeiron is self-sufficient, for it "encompasses everything and governs everything."

Anaximander was not only a philosopher, but also a scientist. He introduced the "gnomon" - an elementary sundial, which was previously known in the East. This is a vertical rod installed on a marked horizontal platform. The time of day was determined by the direction and length of the shadow. The shortest shadow during the day determined noon, during the year - the summer solstice, the longest shadow during the year - the winter solstice. Anaximander built a model of the celestial sphere - a globe, drew a geographical map. He studied mathematics and "gave a general outline of geometry".

is given the question of what such a higher principle of things should be, and comes to the conclusion that only “apeiron” (infinite) can be such. The thought that guided Anaximander when designating the beginning with the word "infinite" is best conveyed in Plutarch's Stromata (10): "the infinite is every cause of every birth and destruction."

What is Anaximander's origin "apeiron" - this is a question that was already solved in antiquity in different ways. In modern times, he gave rise to a whole literature, which received the special name "Anaximander's question."

In our opinion, the answer lies in the very name of the first principle "limitless". Anaximander understands the “infinity” of the first principle primarily in the sense of its inexhaustibility. creative power that creates worlds2. This inexhaustibility of the first principle in the formation of things entails its other properties, and above all its qualitative and quantitative "unlimitedness". Initially there is primary matter, not yet differentiated and therefore qualitatively indeterminate. In the depths of it reigns the balance of opposites. This qualitative uncertainty and indifference of opposites is the second main property of the original

1 "Anaximander's question" in exactly the same way. as the even more famous Platonic Question, was first raised by Schleiermacher (Ueber Anaximandros, 1811).

2 Strumple; Seidel, Teichmüller and Tannery believe that the term "infinite" points primarily to qualitative indeterminacy; Neugeuser. Zeller and J. Bernet relate it primarily to spatial infinity: Natorp - to space-time infinity.

81chala (the first is the inexhaustibility of his creative power). Its third main property is its quantitative infinity (infinity in terms of volume and mass of matter. "Apeiron" Anaximandra is a body with infinite extension; it "embraces" (in the bodily sense) all things, surrounds them from all sides and concludes in Fourthly, it is infinite in time (i.e., eternal). It has not arisen, will not perish, and not only eternal, but also unchangeable (“does not grow old”). , by the absence of qualitative certainty, by the mass of matter and by volume, infinitely in space and time. "Apeiron" means infinity (lack of boundaries) in all conceivable relationship. Anaximander strives for the concept of the infinite in a positive sense, that is, for the concept of the absolute. And he combines1 in his "apeiron" the following concepts: qualitative uncertainty, quantitative unlimitedness, spatial immeasurability, inexhaustibility of creative power, eternity and immutability, and even omnipresent. Apeiron is something more than the first substance from which everything arose, since it is an unchanging, abiding beginning, "which embraces everything and rules everything." It is the source of being and life of the universe. According to the author's intention, apeiron is "absolute"; however, in fact, it does not coincide with the latter concept, since it remains a material, cosmic being.

1 F.Michelis. De Anaximandri infinito disputatio, 1874, as well as N. Hartmann. Platos Logik des Seins, 1909, p. 14-17.

82 "Infinite" is one. It is matter, but not a dead substance, but a living, animate body. Thus, the well-known Aristotelian reproach is also unfair with respect to Anaximander: he puts the driving principle into matter itself, and does not leave it unattended.

Usually there are four main solutions to the Anaximander Question.1

First decision: Anaximander's apeiron is a mechanical mixture (mHMB) of all things. Anaximander only transformed the mythological representation of Chaos (just as Thales proceeded from the mythological image of the Ocean). In ancient times, Bl. Augustine and Irenaeus believed that Anaximander's apeiron is nothing but "migma". In modern times, the main representative of this view is Ritter. Busgen2, Teichmüller, Or. Novitsky, S. Gogotsky and others.

However, it is difficult to reconcile with this understanding the unity and simplicity of Anaximandre's primary substance. If such a mixture can still be represented as a single, homogeneous mass, then it is simply impossible to imagine it as a living whole, as an organic unity.

The second solution: Anaximander's apeiron is something in between the elements, something between the elements (fi mefboe). Aristotle mentions 1) the average between water and air, 2) the average between fire and air, and 3) the average between fire and water as the “average”, taken for the first substance. All these three formulas have found a pre-

1 For a historical development of this issue, with a detailed reference to the literature, cf. at Lutz. Ueber das bursin Anaximanders, 1878.

2 Busgen. Web. das bursin Anaximanders, 1867.

83providers in the understanding of Anaximander's theory of primordial matter. In ancient times, Alexander Aphrodite, Themistius and Asclepius took Anaximander's beginning as a mean between water and air. In modern times, Tidemann, Bule, Krug, Marbach, Heim, Kern, Lutze, architect. Gabriel and others understand the beginning of Anaximander as a bodily, sensually perceived, homogeneous substance, intermediate between water and air. Tannery, according to which Anaximander's apeiron is a gaseous matter saturated with water vapor, can be attributed to the same category. If we proceed from the fact that Anaximander is a student of Thales and a teacher of Anaximenes, then, in fact, the position arises that his apeiron is a substance intermediate between water and air. However, in the historical reconstruction of reality, such a priori constructions are of little value.

The statement that Anaximander's apeiron is a substance intermediate between fire and air, we find in A. Galich, M. Kariysky, Prince. S. Trubetskoy in his "History of Ancient Philosophy", and others. M. Carii, who owns the only Russian special study on Anaximander,1 distinguishes in ancient testimonies a simple middle principle, intermediate between water and air, which he attributes to Arche-lai, and a compound middle principle, intermediate between fire and air, which, in his opinion, should be attributed to Anaximander.

Neugeuser also belongs to the representatives of the theory of "metaksyu". And in his opinion, apeiron

1 M. Carian. Infinite Anaximander. 1890 (Journal of the Min. Nar. Proev. 1890 No. 4-6 and otg. Reviews by E. Radlov in R. Ob. 1890, No. 9 and A. Vvedensky in Questions of Philology and Psychology, book 9).

Anaximander is a simple body that has its own sensuous qualities. Namely, it is the "middle" between the two "first opposites." Such primary opposites in Anaximander are: 1) nature is warm, fiery and light, and 2) nature is cold, wet and dark.

Schleiermacher's controversy was directed mainly against the understanding of the primary substance of Anaximander as "average" between the elements, and after it the number of supporters of this understanding is significantly thinning.

Third solution: Anaximander's apeiron is the future Platonic-Aristotelian matter (elz), which contains all things with their infinite properties potentially (not in reality, but only in possibility). In ancient times, Anaximander Plutarch understood the beginning in this way, in modern times abbe de Canaye, Herbart and his school (apeiron is “pure substance”, according to Strümpel), Krishet, Brandis, Reingold, Beumker, Kinkel, Natorp, etc. Natorp accepts this view on apeiron, as on “gyul”, with the proviso that Anaximander has only the grain of that thought that received a completely definite formula only from Aristotle. This understanding of Anaximander's primary principle, which brings it closer to Plato-Aristotelian matter, suffers from the significant drawback that it loses sight of the main motive of Anaximander's theory of primordial matter: Anaximander strives for the concept of "infinite" in a positive sense, while the Plato-Aristotelian concept of matter ( Z1?) contains the exact opposite motive.

To a large extent, Schlei-

85ermacher, according to which apeiron is a qualityless matter, inaccessible to sensory perception. But Schleiermacher clearly emphasizes the corporeality of Anaximander's primary matter, while Platonic-Aristotelian matter is incorporeal.

J.Burnet also considers Anaximander's apeiron to be a concept related to Aristotelian matter, but at the same time emphasizes significant differences between them. Apeiron of Anaximander is bodily and accessible to sensory perception, although it is a certain prior in relation to all the opposites that form our sensory world.

Fourth decision: Anaximander does not qualitatively define his beginning at all, his apeiron is something completely indeterminate (zeuyt bsiufint). Such a view was held in antiquity by Theophrastus, Cicero, Galen, Sextus Empiricus, Diogenes Laertius, Porfiry, Eusebius, Theodoret, and others; in modern times, Brucker, Windelband, Vorlender, Zeller, and others. According to Zeller, Anaximander simply put forward the position that before all individual things there was an infinite substance, without expressing more definitely about its quality.

These are the four main solutions of the "Anaximander Question" (of which the last one can hardly even be called a "solution", it is rather a rejection of any solution). Each of them refers to Aristotle, each had representatives already in antiquity, and each counts in its ranks outstanding modern historians of philosophy. The fault of such a divergence of views lies primarily with Aristotle, with his vague, confused reports about Anaximander.

There were other, already clearly untenable solutions to the "Anaximander Question". So, Röth says

86that Anaximander's apeiron is nothing but water; author of an article in "Acta phil" XIV St. 1723 and F. Gentskeny say that it is air; Dickinson identifies this principle with atoms, and so on. There were also attempts at an eclectic solution, which found part of the truth in different understandings of Anaximandre's primary matter (Tennemann, Dühring, and others).

Criticism of the various solutions to our problem must proceed primarily from the question of whether the concepts of a later time are not applied to the teaching of Anaximander. With such a study, already the evidence of Aristotle will undergo a radical cleansing. It must be remembered that Anaximander did not yet realize the opposition between mechanism and dynamism, that the problem of the one and the many was first posed by the Eleates, that Anaximander was alien to the Aristotelian distinction between actual and potential, that the concept of a thing and its quality had not yet been quite clearly developed, so that the latter could be denied in the former, that Anaximander did not yet know the four elements, and therefore could not speak of an average between them. Rather, Anaximandrov's "theory of the elements" consisted in the fact that he opposed warm to cold, considering them primary qualities-things (he has not yet differentiated these two concepts). Of course, it would be quite legitimate to raise such questions: how best to translate Anaximander's teaching into the language of the theory of the four elements, or how to express his teaching in terms of the Aristotelian system, or where to attribute this teaching from the point of view of an era in which the opposition between mechanical and dynamic views of nature, and other similar questions

87 questions, if at the same time they were always aware that points of view and concepts alien to it are attached to a given doctrine. So, none of the four main solutions of Anaximander's question ("migma", "metaksyu", "field" and "fusis aoristos") does not seem to us completely satisfactory. In our opinion, the main tendency that guided Anaximander in his theory of the beginning was to escape from the circle of limited qualities-things to the "infinite".

Before parting with Anaximander's theory of primordial matter, we must dwell on one more question: how do all things arise from the "infinite"? Aleiron "selects" them from his bowels. "Isolation" is a purely internal process that takes place in the very first substance, which itself remains unchanged. This process, by means of which the finite emerges from the "infinite", we, together with Kinkel1, are inclined to understand as a phenomenon of spatio-temporal and qualitative determination). Anaximander defines this process neither as a qualitative change in the primary substance, nor as its spatial movement2. However, most historians of philosophy identify it with spatial movement, which they recognize as chaotic, Teichmüller goes even further, accepting the eternal rotational movement of Anaximander's first principle. This view of Teichmüller stands in connection with the data given by him

1 W.Kinkel. Gesch. Der Phil. I Bd. 1906, p.57.

2 The "perpetual motion" of which the doxographers speak is rather an Aristotelian expression for "singling out" and is meant only to oppose Anaximander's teaching to the Eleatics, who completely denied any process in the universe. See J. Burnet, p. 62 and Neuhäuser. an. M., p. 282.

a radically new understanding of Anaximander's "infinite" according to which it is nothing but a world ball, revolving like a wheel; around its axis. Tannery joined Teichmüller. which also identifies the perpetual motion of the "infinite" with the daily rotation of the sky. Unfortunately, these witty hypotheses lack any historical basis.

Everything that is released from the first substance, after a certain period of time, returns back to its mother's womb. Everything finite, individual, emerging from the universal "infinite", is again absorbed by it. In the only fragment of Anaximander that has come down to us, this thought is given an ethical coloring: the return of everything to the infinite is defined as a punishment for guilt. On the question of what is the fault of individual existence, the opinions of historians differ1, and this depends primarily on the discrepancy between the manuscripts2. The most common is the following interpretation: independent individual existence, as such, is an injustice in relation to the "infinite", and for this guilt isolated things pay with death. So, according to the interpretation of the book. S. Trubetskoy3, “everything that is born, arises, everything that is isolated from the universal generic element is guilty by virtue of its very separation and

1 G. Spicker specifically investigates this issue. Dedicto quodam Anaximandri philosophi, 1883 and Th.Zeigler. Ein Wort von An. (Arch. f. g. d. Ph. I., 1888, pp. 16-27).

2 Namely, on whether the manuscript is accepted, in which the word: llulnyt is, or the one in which it is absent.

3 In his Met. in other Greece”; in ancient history. philosophy he adjoins another look. In general, the image of Anaximander in these two works of the prince is very different.

89everything will die, everything will return to her.” According to Schleiermacher, every thing pays for the joy of its existence with death. According to this view, everything individual contains injustice in its very existence. But the reason for the existence of individual things is in the infinite. This is his fault.

If individual things are punished not for what they themselves have done, but for their very existence, then they rather atone for the guilt of the first principle, which consists in the ever-living, never ceasing desire in it to give birth to all new things. Neugeuser already partially notices this side, according to which the emergence of individual things is the mutual injustice of the primary substance in relation to the things distinguished by it and the latter in relation to the primary substance from which they are isolated. The origin is to blame for letting them out of itself, while the things are guilty for the fact that they stood out from the original unity. Mutual guilt must be redeemed by both parties: the punishment of things is that they return to their original unity, the punishment of the beginning is that it takes them back into itself. The religious and metaphysical interpretation of Anaximander's fragments is also given by Teichmüller, according to whom Anaximander portrayed the entire world development as a divine tragedy in the spirit of patripassianism.

Another group of historians of philosophy holds the view that Anaximander's fragment deals with the injustice and guilt of individual things in relation to each other (blüllum). For most of them, the meaning of the fragment is not religious-metaphysical, and not even moral, but purely cosmic, and the very words "injustice"

They tend to understand "guilt" and "punishment" as poetic metaphors. Thus, Spicker conveys the meaning of the fragment as follows - all things return, according to the necessity lying in their nature, to that from which they arose, so that an equation of opposites constantly occurs. According to J. Burnet, Anaximander in his doctrine of primordial matter proceeds from opposition and struggle between things. The predominance of any thing would be injustice. Justice requires a balance between all opposites. According to Ritter, the injustice of separating elements from the infinite lies in the uneven distribution of heterogeneous elements (some elements seem to be offended by others). According to Byck "y, the injustice of individual existence consists in the elevation of one part above the other. According to Schwegler, the existence, life and activity of independent finite things is a violation of the calm, harmonious coexistence of things in the fundamental principle and consists in their mutual enmity. Also, according to Zeller, the fragment speaks of the mutual injustice of things relative to each other. A very special position is taken by Ziegler, who believes that all things are punished for human injustice. Thus, according to his interpretation, all nature is punished for the guilt of people. Understanding the fragment in a purely moral sense, Ziegler deduces from this the consequence that Anaximander was the first of the pre-Socratics to connect metaphysical speculation with ethical reflection. We would prefer to follow the best handwritten tradition adopted by G. Diels, which retains the word llulpit, but at the same time we think that the religious-metaphysical

The meaning corresponds more to the general spirit of Anaximander's teaching than the cosmic and purely moral one. And so we interpret the meaning of the fragment as follows: individual things receive punishment and retribution from each other for their wickedness. For Anaximander, the sensible world is a world of opposites that destroy each other. So, first of all, primary elements destroy each other - “cold” and “warm”, also “light” and “dark”, “fiery” and “wet”, etc. (for Anaximander every quality is an eo ipso thing). Animals eat each other. A thing that disappeared in this way (moreover, any change in quality is considered as the disappearance of some thing) was not completely destroyed, but it did not pass into another sensible thing either. She returned to the omnipresent origin, which instead of her singled out another thing from its bowels - quality. Thus, "llulpit" indicates only a method of punishment, and not the basis of guilt, which Anaximander saw rather in the individual isolation of a thing both from the original principle and from other things, the consequence of which is also the mutual enmity of all things among themselves and their wickedness in relation to to the divine source.

The never-ending process of "allocation" and "absorption" of everything constitutes the life of the universe, which Anaximander imagines as a huge animal (typn). Similarly, different parts of the universe: separate worlds, luminous

1 In Greek, “to be punished by someone” is equally well rendered dYachzn didnby fyanya and er fynpt. Thus, our understanding deviates from G. Diels, according to which llylpit is dativus commodi.

92la, etc., are animals (thus, he calls our sky a fiery bird).

These are the main philosophical views of Anaximander. His merits in the field of individual sciences are as follows.

In mathematics, Anaximander did not make any new discoveries; he is only credited with systematizing all the positions of geometry established before him (the first "outline of geometry").

In cosmology, his doctrine of innumerable worlds should be noted. In contrast to those historians (Zeller, Teichmüller, Tannery), who see here an indication of an infinite series of worlds, following friend after another in time (and at any moment there is only one world), we believe that here we are talking about an infinite number of simultaneously coexisting worlds, isolated from each other. This is precisely how the teachings of Anaximander were understood in antiquity (Simplicius, Augustine, and others), and among the latest historians, Busgen, Nenhauser, J. Burnet, and others adhere to this view.

In astronomy, the beginnings of the Pythagorean theory of spheres go back to Anaximander. He taught that three rings of fire2 surround the earth, which occupies a central place in our world: the solar ring, which is farthest from the earth, the lunar one, located in the middle, and the stellar one, closest to the earth. These rings are covered with air

1 This, of course, does not exclude the idea of an endless periodic change of individual worlds, arising and collapsing, which is also found in Anaximander.

2 According to Brandis and Zeller, these are not circles (as other historians think), but cylinders that look like wheels.

3 Anaximander arranges them according to the strength of light, believing that the brightest, like the purest fire, should be located farthest from the earth and closest to the periphery of our world.

93 shells that hide the fire contained in them. But there are round holes in the rings through which the fire enclosed in them escapes; these streams of fire are the essence of the sun, moon and stars that we see. Solar and lunar eclipses, and likewise the phases of the moon are explained by the temporary blockage of these openings. Anaximander calculates the diameters of the celestial rings, the distances of the stars, their magnitude and movement. According to Diels1, all these numerical calculations come from the religious and poetic mysticism of numbers, so that here scientific motives are intricately intertwined with religious and mythological ideas. In Anaximander we find the first sketch of the theory of spheres, according to which the celestial spheres revolve around the earth, as the center of the world, carrying away the luminaries that are on them. This geocentric theory of spheres, which prevailed in antiquity and the Middle Ages, we are accustomed to consider as a brake on the movement of scientific thought, bearing in mind the heliocentric theory that appeared to replace it. However, I will ask the reader to put aside this preconceived notion here and judge it by the distance that separates it from the astronomical notions that preceded it. Anaximander, on the other hand, had to depart from the following

1 H. Diels. Web. Anaximanders Kosmos (Arch. f. G. d. Ph. X, 1987, pp. 232ff.)

2 According to Sartorius "a (Die Entwickiung der Astronomic beiden Griechen bis Anaxogoras und Empedocles, 1883, p. 29), Anaximander attributed two kinds of movement to the solar ring at the same time: 1) around the world center - the earth from east to west and 2) annual movement around its center, due to which the sun, located on the periphery of the solar ring, deviates either north or south of the equator (to explain the solstices).

94the future picture of the world that prevailed before him1. The earth is a flat disk; around it flows the Ocean, which in its form is a steep, closed in itself, of relatively small width. Above the earth - the sky, which has the shape of a hemisphere. The radius of the celestial hemisphere is equal to the radius of the earth (therefore, the Ethiopians, who live in the extreme east and west, are black from the proximity of the sun). The sky is motionless, the luminaries on it rotate: they rise from the Ocean, pass through the sky and again plunge into the waters of the Ocean.

If we compare the astronomical theory of Anaximander with those ideas from which he had to start, then such a historical assessment of it, we think, will be high.

Apart from a number of other astronomical discoveries(of which his notion of large sizes celestial bodies), Anaximander also owns an attempt to explain meteorological phenomena: wind, rain, lightning and thunder. According to legend, he predicted an earthquake in Lacedaemon.

He is also credited with the introduction in Greece of the gnomon (an instrument used to determine the noon and solstice) and the sundial. Likewise, he was the first to make a model of the celestial sphere.

Anaximander also has important merits in the field of geography. He owns the first geographical map, which was an image of the entire surface of the earth according to the then

1 See Sartorius I., pp. 14 et seq., Tannery, p. 78. Homer, Hesiod, and Thales equally share this view of the world. The whole difference between them is that, according to Homer and Hesiod, Tartarus is under the earth, while Thales thought that the earth rests on water.

95 ideas about her. Based on this work of Anaximander, half a century later, Hecataeus wrote the first essay on geography. According to Anaximander, the earth is a flattened ball or cylinder, the height of which is equal to a third of the base (it looks like a drum in shape). The earth hangs motionless in the center of the world due to the fact that it is equally separated from all ends of the world. Thus, Anaximander first expressed the idea that the earth, surrounded on all sides by air, hangs freely, without any support. He already knows that there is no absolute up and down in the world.

Finally, a very important phenomenon in the history of thought is the cosmogony of Anaximander. In him we find a purely natural explanation of the formation of our entire universe, and thus his cosmogony is the first forerunner of the Canto-Laplace hypothesis. In the doctrine of the origin of man, Anaximander is the forerunner of Darwin. The first animals, according to his teachings, arose from the water and were covered with scales. Later, some of them, having moved to the land, were transformed according to the new conditions of life. And the race of people arose from another species of animals, the proof of which, according to Anaximander, is the long childhood of man, during which he is helpless. According to legend, Anaximander forbade the eating of fish, "since the fish is our progenitor.

In addition to the philosophical essay "On Nature",; Anaximander was credited with several works on astronomy.

1 It is expounded in detail by Neugeuser, Teichmüller and Tannery.

961. Diogenes Laertius II 1-2 (1). Anaximander of Miletus, son of Praxias. He said1 that the beginning and element (element) is the Infinite2, without defining it either as air, or as water, or as anything else. He taught that the parts change, but the whole remains the same. The earth rests in the middle, occupying the center of the world, and is spherical in shape. (The moon has a borrowed light, namely, its light from the sun3, while the sun is no less than the earth and is the purest fire.)

(As Favorinus reports in his History of Miscellaneous Things, he was the first to discover the gnomon4, indicating the solstices and equinoxes, and installed it in Lacedaemon on a plane grasping the shadow, and also built a sundial.)

(2) Likewise, he was the first to draw the surface of the earth and the sea, and he also built the (celestial) sphere (globe).

He compiled a summary of his positions, which, probably, was still in the hands of Apollodorus of Athens. Namely, the latter says in his "Chronicle" that Anaximander was 64 years old in the second year of the 58th Olympiad5 and that he died soon after (the heyday of

1 The beginning (before brackets) is a superficial excerpt from Theophrastus.

2 Since there is no member in the Russian language, then to indicate the difference between the “infinite”, as a principle (fi breyspn), from a similar adjective, we will write it with a capital letter.

5 This teaching of Anaxagoras about the light of the moon is erroneously attributed by Laertius to Anaximander

4 Gnomon - a vertical rod, mounted on a horizontal plane.

5 In the work of Anaximander, autobiographical information was given, which was used by Apollodorus.

97his forces completely coincided with the tyranny of Polycrates of Samos1).

(They say that once the children laughed at his singing, but he, having learned about this, said: “So, for the sake of the children, we must sing better” 2.)

There was another Anaximander, a historian, also a Milesian who wrote in the Ionian dialect.

2. Seida. Anaximander, son of Praxias, Milesian philosopher, relative, disciple and successor of Thales. He was the first to discover the equinox, the solstice and the sundial, and the first to state that the earth lies in the very center. He also introduced the gnomon and gave a general outline of all geometry. He wrote essays: "On Nature", "Map of the Earth", "On the Fixed Stars", "Globe" and some others.

3. Aelius V. H.III 17. Anaximander led the migration from Miletus to Apollonia [on Pontus].

4. Eusebius P.E.X 14. 11. The disciple of Thales is Anaximander, the son of Praxias, also a Milesian by birth. He was the first to build gnomons that serve to determine the solstices, times, hours and equinoxes.

Wed. Herodotus II 109 (translated by F. Mishchenko). As for the sundial, the solar indicator, and the division of the day into twelve parts, the Hellenes borrowed all this from the Babylonians.

5. Pliny N.H.II 31. According to legend, Anaximander of Miletus was the first in the 58th Olympiad to comprehend the inclination of the zodiac and thus laid the first foundation for its knowledge, then Cleostratus discovered the signs of the zodiac, and it was precisely the former

1 According to G. Diels, the last message should be attributed to Pythagoras.

2 Diels considers this anecdote to be fiction.

Most of all, the signs of Aries and Sagittarius, the very (heavenly) sphere was discovered much earlier by Atlas.

5a. Cicero de div. 150.112. The physicist Anaximander persuaded the Lacedaemonians to leave their homes and city and settle down in the field in view of the imminent onset of an earthquake. It was the same earthquake when the whole city was destroyed, and the top like a stern was torn off Mount Taygetus.

6. Agathemer I 1 (from Eratosthenes). Anaximander of Miletus, a disciple of Thales, was the first to dare to draw the earth on a board, and after him Hecateus of Miletus, a wandering husband, did the same with the greatest care, so that his work aroused (general) surprise.

Strabo I p. 7. Eratosthenes says that the first (geographers) after Homer were the following two persons: Anaximander, friend and fellow citizen of Thales, and Hecateus of Miletus. Namely, Anaximander published the first geographical map Hecateus left behind a work (on geography), whose belonging to him is certified from his other work.

7. Themistius or. 36r. 317. Of those Hellenes whom we know, he was the first to dare to publish a written essay on nature.

Z. Diogenes VII 70. Diodorus of Ephesus writes about Anaximander that [Empedocles] imitated him, embellishing (his work) with high-flown vague expressions and wearing magnificent clothes.

9. Simplicius pbys. 24, 13 (from Theophrastus Opinions of the Physicists, fr. 2 Doc. 476). Of those who taught that (the beginning) is a single moving infinite, Anaximander of Miletus, the son of Praxias, the successor and student of Thales, expressed (the position) that the beginning (principle) and element (element) of being

99 is the Infinite, the first to introduce such a name for the beginning. He says that the beginning is not water, and in general none of the so-called elements (elements), but some other infinite nature from which all the heavens and all the worlds in them arise. “And from which all things arise, in the same they are resolved according to necessity. For they are punished for their wickedness and receive recompense from one another in set time", he says in overly poetic terms. Obviously, noticing that the four elements turn into one another, he did not consider it possible to recognize any one of them underlying the others, but accepted (as a substratum) something different from them. According to his own teaching, the emergence of things does not come from a qualitative change in the element (element), but due to the fact that opposites stand out due to perpetual motion. That is why Aristotle placed him next to the followers of Anaxagoras. 150. 24. The opposites are warm and cold, dry and wet, and so on.

Wed. Aristotle pbys. A 4 187 a 20. Others believe that the opposites contained in it stand out from the one. Thus says Anaximander and all who acknowledge the One and the Many, such as Empedocles and Anaxagoras. For, according to them, everything else stands out from the mixture.

In the passage cited by Simplicius, the fragment of Anaximander with all the features of his style is preserved. Simplicius only gave it the form of indirect speech. Here are two other Russian translations of the fragment.

1 Most people mistranslate this passage: “the first one to enter the word beginning.”

100Per. book. S. Trubetskoy1. “To those beginnings from which all things have their origin, to those same they are destroyed by necessity, in punishment and expiation, which they pay each other for untruth, according to a certain order of time.”

Per. G. Tsereteli. From this (beginning) all things receive birth and, according to necessity, destruction, because at a certain time they undergo punishment and (bear) retribution for mutual injustice.

9a. Simplicius Pbys. 154, 14- And Theophrastus brings Anaxagoras closer to Anaximander and interprets the teaching of Anaxagoras in such a way that it turns out that the latter could speak of the substratum as of a single nature. Namely, he writes in the History of Physics the following:

“So, with such an interpretation of his (Anaxagoras) teaching, one might think he considers material causes to be infinite (in number), as mentioned above, and the cause of movement and birth is one. But if we accept that the mixture of all things is a single nature, indefinite in form and magnitude - and this, apparently, he wants to say - then we will have to attribute to it two principles: the nature of the infinite and the mind, and thus it will turn out to be that he represents the material elements in exactly the same way as Anaxi-mander.

10. [Plutarch] Stromata 2 (D. 5 79; from Theophrastus). After him [Thales], Anaximander, a friend of Thales, asserted that in the Indivisible lies every cause of creation and destruction.

1 According to the book. S. Trubetskoy, individual things return to their elements and only the latter are absorbed by the infinite.

Detail of The School of Athens by Raphael (1509)

Anaximander Quotes: 1. Ayperon is one and absolute, immortal and indestructible, which encompasses everything and rules everything. 2. The Infinite (iperon) is every cause of every birth and destruction. 3. From the one, the opposites contained in it stand out. 4. The infinite is the beginning of being. For everything is born from it and everything is resolved into it. That is why an infinite number of worlds arise and resolve back into that from which it arises. 5. The number of worlds is infinite and each of the worlds (arises) from this infinite element. 6. Countless heavens (worlds) are gods. 7. Parts change, but the whole is unchanged. 8. The first animals were born in moisture and were covered with prickly scales; upon reaching a certain age, they began to go out on land, and there, when the scales began to burst, they soon changed their way of life.

Professional, social position: Anaximander was a Greek philosopher, a pre-Socratic, who lived in Miletus, a city in Ionia.

Main contribution (what is known): Anaximander was one of the greatest minds that ever lived on earth. He is considered the first metaphysician. He also pioneered the application of scientific and mathematical principles to the study of astronomy and geography.

Contributions: He proposed the first transcendental and dialectical approach to nature and a new level of conceptual abstraction. He argued that physical forces, not supernatural entities, create order in the universe.

Neither water, nor any other elements, are first principles. At the heart of everything is "apeiron" - ("unlimited" or "indefinable"), an infinite, unperceivable substance from which all the heavens and numerous worlds within them arise.

Apeiron always existed, filled all space, encompassed everything and was in constant motion, dividing from the inside into opposites, for example, into hot and cold, wet and dry. Opposite states have a common basis, being concentrated in a certain unity, from which they are all singled out.

The first version of the law of conservation of energy."Apeiron" causes the movement of things, many forms and differences are produced from it. These multiple forms return to infinity, to the diffuse immensity from which they arose. This endless process of arising and disintegration is inexorably carried out throughout the ages.

Cosmology. He argued that the Earth remained unsupported at the center of the universe because there was no reason to move it in any direction.

He discovered the tilt of the ecliptic, the celestial globe, the gnomon (to determine the solstice), and also invented the sundial.

Cosmogony. He suggested that the worlds arose from an unchanging and eternal reservoir, in which they are eventually absorbed. In addition, he anticipated the theory of evolution. He said that man himself, man and animals arose in the process of transmutations and adaptation to environment.

His new ideas:

Apeiron is the first element and principle.

He never gave a precise definition of apeiron, and he, in general (for example, Aristotle and St. Augustine) was understood as some kind of primitive chaos. In some respects, this concept is analogous to the concept of "abyss", which occurs in the cosmogony of the East.

He first proposed the theory of Multiple Worlds and populated them with various gods.

In his opinion, man reached his modern state by adapting to the environment, believed that life developed from moisture and that man originated from fish.

He said that the earth has cylindrical shape, and the depth of the cylinder is equal to one third of its width.

According to Themistius, he was "the first known Greek to publish a written document on nature".

Anaximander was the first Greek to draw a geographical map of the Earth.

He was the first to introduce the term "law", applying the concept of social practice to nature and science.

He was the first to lay the foundation for the dialectical concepts of subsequent philosophy - he proposed the law of "the unity and struggle of opposites." In his opinion, apeiron, as a result of a vortex-like process, is divided into physical opposites hot and cold, wet and dry.

Main works:"On Nature" (547 BC) - the first written document in Western philosophy. Earth rotation, Sphere, Geometric measurements, Map of Greece, Map of the World.

Origin: Anaximander, son of Praxiades, was born at Miletus during the third year of the 42nd Olympias (610 BC).

Education: He was a student and companion of Thales. He was influenced by Thales's theory that everything comes from water.

Influenced on: Thales

The main stages of professional activity: He was a student and companion of Thales and the second master of the Miletus school, where Anaximenes and Pythagoras were his students.

Anaximander took part in the creation of Apollonia on the Black Sea and traveled to Sparta.

He also took part in political life Miletus and was sent as a legislator to the Miletus colony of Apollonia, located on the Black Sea coast (now Sozopol, Bulgaria).

The main stages of personal life: Only a small part of his life and work is known to researchers today. He may have traveled a lot. He exhibited stately manners and wore pompous clothes.

Zest: He believed that things for a while, "in debt", acquire their being and composition, and then, according to the law, at a certain time, return the debts to the principles that gave rise to them. It is believed that Thales may have been his uncle.

All things arise from the infinite...

Anaximander

Thales with his idea of systematic development natural sciences became for the Greeks a great pioneer in the field of thought. But modern scholars would rather choose his successor, the more poetic and passionate Anaximander, as their hero. He can truly be called the first real philosopher.

Anaximander went beyond the brilliant but simple assertion that all things are made of the same matter, and showed how deeply the means of objective analysis must penetrate into real world. He made four well-defined major contributions to people's understanding of the world:

1. He realized that neither water nor any other ordinary substance like it can be the basic form of matter. He imagined this basic form - rather vaguely, though - as a more complex boundless something (which he called "apeiron"). His theory has served science for twenty-five centuries.

2. He transferred the concept of law from human society to physical world, and it was complete break with the old notions of capricious anarchist nature.

3. He was the first to use mechanical models to help understand complex natural phenomena.

4. He concluded in rudimentary form that the earth changes over time and that higher forms of life could develop from lower ones.

Each of these contributions by Anaximander is a discovery of the first magnitude. We can get an idea of how important they are if we mentally remove from our modern method of thinking everything connected with the concepts of what is neutral matter, the laws of nature, the computing apparatus of scales and models, and what evolution is. In this case, little would be left of science and even of our common sense.

Anaximander was from Miletus and was born about forty years after Thales (hence, his mature activity should have begun around 540 BC). They wrote about him that he was a student of Thales and replaced his teacher in the Milesian school of philosophy. But both the date and this information are based on later reports, which are not chronologically accurate and transfer the idea of schools organized according to a certain system to the early period of ancient Greek thought, when in reality there were no such formal associations of philosophers and scientists. However, we can be sure that Anaximander was a junior countryman of Thales, realized and highly appreciated the novelty of his ideas and developed them - exactly as has already been said. Anaximander was a philosopher in the sense that, among the things that interested him, he dealt with philosophical questions; but in that early period philosophy and science were not yet divided into separate areas. It is better for us to consider Anaximander an amateur than to follow the assumptions of later historians, who carried over their idea of a professional philosopher.

We can add little to the already mentioned information about his hometown, time of life and acquaintance with Thales. Anaximander was versatile and practical person. The Milesians chose him as the head of the new colony, which indicates his important role in political life. It is believed that he traveled widely, and this may be confirmed by three facts of his biography: he was the first Greek geographer to draw a map; one of his trips - from Ionia to the Peloponnese - is confirmed by evidence that he created in Sparta a new instrument in the form of a sundial that measured the length of the seasons; the fact that he saw fossilized fish high in the mountains suggests that he probably climbed the mountains of Asia Minor and carefully peered at what he saw around. Adding to this the tradition of Miletus, the birthplace of engineers, and the fact that Anaximander applied technological methods when he designed tools, maps and models, we can also assume that he, like Thales, was at least an expert in engineering, and possibly even professional engineer.

Anaximander's first major contribution to science was his new method analysis and the concept of "matter". He agreed with Thales that everything in the world consists of a single substance, but believed that it could not be any substance familiar to humans like water, rather it was a “limitless something” (apeiron), in which initially contained all the forms and properties of things, but which itself did not have any specific features characteristic of it.

At this point, Anaximander made an interesting move in his reasoning: if everything that exists in reality is matter with certain properties, this matter should be able to be hot in some cases, cold in others, sometimes wet, and sometimes dry. Anaximander believed that all properties of matter are grouped into pairs of opposites. If we identify matter with one property from such a pair, as Thales did when he said “all things are water”, then the conclusion will follow from this: “to be means to be wet. What then happens when things become dry? If the matter of which they are composed is always wet (as Anaximander defined the Thales word guidor), desiccation would destroy the matter in things, they would become immaterial and cease to exist. In the same way, matter cannot be identified with any one quality and thus exclude its opposite. From this it follows that matter is something boundless, neutral and indefinable. From this "reservoir" opposite qualities are singled out: all concrete things arise from the infinite and return to it when they cease to exist.

This is a movement of philosophical thought from the primitive definition of matter as guidor(water) to understanding matter as an infinite substance is a huge step forward. Indeed, until the 20th century, in the science and philosophy of modern times, matter was often described as a "neutral substance", which is very similar to Anaximander's "apeiron". But between modern idea and its ancient progenitor there is one fundamental difference: Anaximander did not yet know the difference between the image that the imagination creates and the abstract mental construction. The truly abstract concept of matter did not appear until two hundred years after Anaximander, when the atomistic theory was created. Anaximander could well associate the infinite with the image of a gray fog or a dark haze at sunset, or hills of indefinite outlines on the horizon. Nevertheless, this attempt to define matter - the basis of all physical reality - led directly to those later, more perfect schemes that we find when materialism arises as a fully developed philosophical system.

Anaximander's introduction of models into astronomical and geographical research was an equally important turning point in the development of science. Very few people understand how important models are, although we all use them and cannot do without them. Anaximander tried to design objects by reproducing their inherent linear relationships, but on a smaller scale. One result of this was a pair of maps: a map of the earth and a map of the stars. The map shows the distances to various places and the direction in which you need to move to them. If people had to find out where other cities and countries are from the diaries of travelers and their own impressions, then travel, trade and geographical research would be very difficult activities. Anaximander also built a model that reproduced the movements of the stars and planets; it consisted of wheels that rotated with different speeds. Like projections in our modern planetariums, this model made it possible to accelerate the apparent movement of the planets along their trajectories and find patterns and certain speed ratios in it. To briefly explain how much we owe to the use of models, it suffices to recall that Bohr's atomic model played a key role in physics and that even a chemical experiment in a test tube or an experiment on rats in biology is an application of modeling techniques.

The first astronomical model was quite simple and unsophisticated, but for all its primitiveness, it was the progenitor of the modern planetarium, mechanical clocks, and many other related inventions. Anaximander suggested that the earth is disc-shaped, located at the center of the world and surrounded by hollow tubular rings (a modern chimney is a good semblance of what he had in mind) different sizes that rotate at different speeds. Each tubular ring is full of fire, but itself consists of a hard shell like a shell or bark (this shell Anaximander calls floyon), which allows the fire to burst out only from a few holes (breathing holes from which the fire bursts out as if blown by blacksmith bellows); these holes are what we see as the sun, moon and planets; they move across the sky as the circles revolve. Between the round wheels and the earth are dark clouds that cause eclipses: an eclipse occurs when they close the holes in the pipes from our eyes. This whole system as a whole rotates, making a revolution in one day, and, in addition, each wheel moves by itself.

It is not entirely clear whether this model had such an interpretation for fixed stars as well. It seems that Anaximander constructed a globe of the sky, but we do not know how this expansion of the technique of maps and models was connected with the moving mechanism of rings and fire.

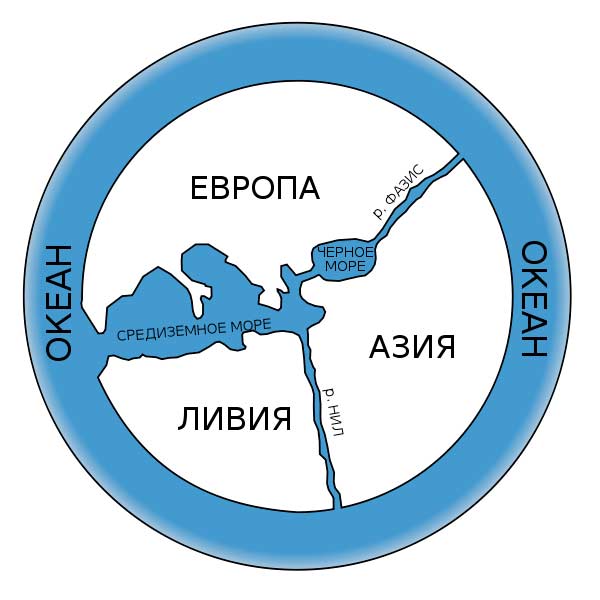

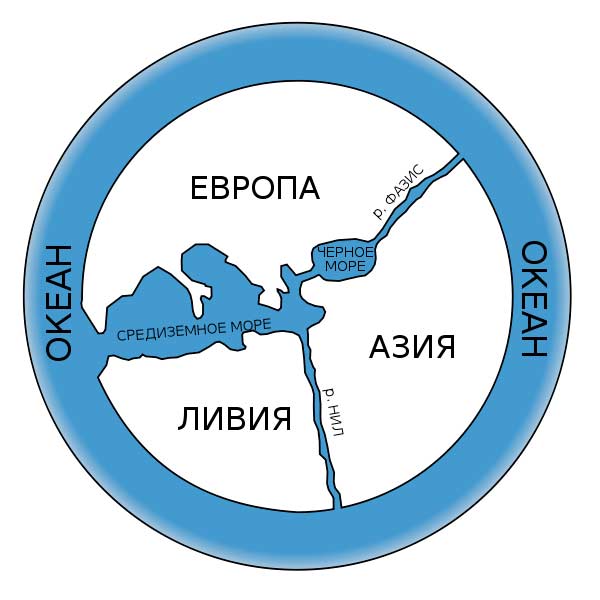

This map is a reconstruction of what is believed to be the first map ever drawn. geographical map. Its center is Delphi, where a stone called "the navel of the earth" (in Greek "omphalos") marked the exact center of the earth. The cartographer who created it was Anaximander, a Greek philosopher who lived from about 611 to 547 BC. e. Early maps were all round. Half a century later, Herodotus commented as follows: “I find it funny to see that so many people still draw maps of the Earth, but not one of them depicted it even tolerably: after all, they drew the Earth round, as if it were made with a compass, and surrounded it ocean river.

Anaximander's great contribution to science was the general conception of models, which he applied in the same way that we apply them now. In drawing the first map of the world known to him, he showed the same combination of technical ingenuity and scientific intuition. Just as a moving model can show the ratios of long astronomical periods on a smaller scale where they are easy to observe and control, a map is a model of the distances between objects and their relative position on a smaller scale, so that a person can take in it all at a glance; the map saves him from having to travel for long months or trying to sort through scattered notes where travelers described their routes in order to determine the location of places, distances and direction of movement.

The idea of a map is in itself an indication of the love of clarity and symmetry that was characteristic of Greek science and of later classical maps and models. Anaximander's world had the form of a circle centered on Delphi (where the sacred stone omphalos, as the Greeks believed, marked the exact center of the universe) and was surrounded by the ocean. Like the wheels - "chimneys", this map became the primitive ancestor of a huge offspring: it is the progenitor of maps and drawings that made possible the existence of modern navigation, survey work in geography and geology. The "Map of the Stars" is perhaps an even clearer example of how this original, scientific, ancient mind worked: the thought of charting the sky instead of looking at the patterns the stars form as omens or ornaments implies, that terrestrial and celestial phenomena are of the same nature, and signifies an attempt to understand the world not by means of aesthetic fantasy and not by the irresponsible way of religious superstition.

But this use of models to duplicate the studied patterns of nature, however enormous their role has been over the centuries since then, is just a side addition to the more general idea that nature is regular and predictable. Anaximander expressed this idea in his definition of natural law: "All things arise from the infinite ... they compensate each other for damage, and one pays the other for her guilt before her when she commits injustice, according to the account of time."

Although Anaximander seems to be repeating the ideas of high tragedy, in which "hybris" (excess of pride) inevitably leads to "nemesis" (fall-retribution), he speaks in purely legal language, borrowed from judicial practice where the harm that one person causes to another is compensated by the payment of money. Here he uses as a model for the periodic change of natural phenomena not a clock, but a pendulum. “All the things” that break the law in turn and pay the price for it are those opposite qualities that are “singled out” from the infinite. Events in nature, in fact, often take the form of a constant movement from one extreme state to another, opposite, and back; illustrative examples of this - ebb and flow, winter and summer. This movement became the model for Anaximander's "laws of nature": one quality tries to develop more than it should, displacing its opposite, and therefore "justice" throws it back, punishing for intrusion into someone else's territory. But over time, that of the opposites that lost at the beginning becomes stronger, in turn crosses the forbidden line and, "according to the account of time", must be returned to its legal limits.

This was a huge advance compared to the world of Thales, where the individual "psyches" of things were responsible for change and movement, although the tendency to endow everything with human properties and mythological thinking did not completely die out. From a historical point of view, it is interesting that the definition of the law of nature arose as a transfer to another area of the idea of \u200b\u200bjurisprudence already established in society: we would rather expect the opposite, since nature seems to us much more ordered than human society. However, the code of laws seemed to Anaximander to be the best model he could find to explain his new intuitive idea of the exact periodicity and regularity of the natural order.

The idea of evolution of Anaximander was led by acquaintance with the fossilized remains of fossil animals and observation of babies. High in the mountains of Asia Minor, he saw fossilized marine animals in the thickness of the stone. From this, he concluded that these mountains were once in the sea, under water, and that the level of the ocean was gradually lowering. We see that this was a special case of his law of alternation of opposites: the spill and drying of spilled water. He correctly reasoned that if once the whole earth was covered with water, then life must have originated in this ancient ocean. He said that the first and simplest animals were "sharks". We have no explanation why they were, but probably because, firstly, sharks seemed to him similar to the fossil fish that he saw, and, secondly, the very tough skin of sharks seemed to him a sign of primitiveness. Looking at human children - he had at least one son of his own - he came to the conclusion that no such helpless living creature could survive in nature without a protective environment. Life on land evolved from sea life: as the water dried up, the animals adapted to it by growing spiny hides. But people, because of their long helplessness in childhood, needed some additional process. But before this task, Anaximander was at an impasse: he could only assume that people, perhaps, developed inside the sharks and were released from them when the sharks died, and by that time they themselves had become more capable of independent life.

In his reflections on biological and botanical topics, Anaximander expressed another original idea: that in all nature, beings that grow do so in the same way. They grow in concentric rings, the outermost of which hardens and turns into "bark" - tree bark, shark skin, dark shells around fiery wheels in the sky. It was a way to bring together developmental phenomena found separately in astronomy, zoology and botany; but this "shell" theory, unlike the other ideas we have considered here, has never been taken seriously. Later philosophers and men of science, from ancient Greeks to modern Americans, took either physics or zoology as their model of what science should be (extreme cases: respectively the simplest and most difficult subject to study). And Anaximander's statement is more like a generalizing conclusion from botany.

Anaximander, who combined the inquisitiveness of a scientist, the rich imagination of a poet, and the ingenious bold intuition, can undoubtedly share with Thales the honor of standing at the origins of Greek philosophy. After Anaximander, Greek thinkers were able to see that the new questions posed by Thales implied something that went far beyond the answers offered by both Thales and Anaximander himself. We seem to see how science and philosophy froze for a moment in front of a new world that had just opened up for them - the world of abstract thought, which was waiting for its researchers.