Bell pepper is a wonderful tasty and healthy vegetable that you can ...

"Lenta.ru" studies the so-called "controversial issues" of Russian history. Experts preparing a unified school textbook on the subject formulated theme number 16 as follows: "The reasons, consequences and assessment of the fall of the monarchy in Russia, the coming to power of the Bolsheviks and their victory in the Civil War." One of the key figures in this topic is the last Russian emperor Nicholas II, who was killed by the Bolsheviks in 1918, and at the end of the twentieth century, canonized by the Orthodox Church. "Lenta.ru" asked the publicist Ivan Davydov to study the life of Nicholas II in order to figure out whether he could be considered a saint and how the tsar's private life was connected with the "catastrophe of 1917".

In Russia, history ends badly. In the sense that it is reluctant. Our history continues to weigh on us, and sometimes on us. It seems that in Russia there is no time at all: everything is relevant. Historical characters are our contemporaries and participants in political discussions.

In the case of Nicholas II, this is quite clear: he is the last (at least for the moment) Russian tsar, he began the terrible Russian XX century - and the empire ended with him. The events that determined this century and still do not want to let us go - two wars and three revolutions - are episodes of his personal biography. Some even consider the murder of Nicholas II and his family to be a nationwide unrequited sin, for which many Russian troubles are the payment. Rehabilitation, search and identification of the remains of the royal family are important political gestures of the Yeltsin era.

And since August 2000, Nicholas has been a canonized holy passion-bearer. Moreover, he is a very popular saint - suffice it to recall the exhibition "The Romanovs" that took place in December 2013. It turns out that the last Russian tsar is in spite of his murderers and is now more alive than all the living.

It is important to understand that for us (including those who see the last tsar as a saint) Nicholas is not at all the person he was for millions of his subjects, at least at the beginning of his reign.

In collections of Russian folk legends, a plot akin to Pushkin's "The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish" is repeatedly repeated. A peasant goes for firewood and finds a magic tree in the forest. The tree asks not to destroy it, promising various benefits in return. Gradually, the old man's appetites (not without incitement from the quarrelsome wife) grow - and in the end he declares his desire to be a king. The magic tree is horrified: is it a conceivable thing - a king from God has been placed, how can you encroach on such a thing? And turns a greedy couple into bears so that people are afraid of them.

So, for his subjects, and by no means only for the illiterate peasants, the tsar was the anointed of God, the bearer of sacred power and a special mission. Neither revolutionary terrorists, nor revolutionary theoreticians, nor liberal free-thinkers could seriously shake this belief. Between Nicholas II, the anointed of God, crowned in 1896, the sovereign of all Russia - and the citizen Romanov, whom the Chekists killed in Yekaterinburg with his family and loved ones in 1918, there is not even a distance, but an insurmountable abyss. The question of where this chasm originated from is one of the most difficult in our history (not particularly smooth at all). Wars, revolutions, economic growth and political terror, reforms, reaction - everything is linked in this issue. I will not deceive - I have no answer, but there is a suspicion that some small and insignificant part of the answer is hidden in the human biography of the last bearer of autocratic power.

Many portraits have survived: the last tsar lived in the era of photography and himself loved to photograph. But words are more interesting than muddy and old pictures, and a lot has been said about the emperor, moreover by people who knew a lot about the arrangement of words. For example, Mayakovsky, with the pathos of an eyewitness:

And I see - the landau is rolling,

And in this landa

A young military man is sitting

In a sleek beard.

Before him, like lumps,

Four little girls.

And on the backs of the cobblestones, as on our coffins,

The retinue behind him in eagles and in coats of arms.

And the bells ringing

Lost in a lady's squeak:

Urrrah! Tsar-Emperor Nicholas,

Emperor and autocrat of all Russia.

(The poem "The Emperor" was written in 1928 and is dedicated to an excursion to the burial place of Nicholas; the poet-agitator, of course, approved of the murder of the tsar; but the poetry is beautiful, nothing can be done about it.)

But that’s all later. In the meantime, in May 1868, a son, Nikolai, was born in the family of the heir to the throne, Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich. In principle, Alexander Alexandrovich was not preparing to reign, but the eldest son of Alexander II, Nicholas, fell ill during a trip abroad and died. So Alexander III became tsar, in a sense, by accident. And Nicholas II, it turns out, is doubly accidental.

Alexander Alexandrovich ascended the throne in 1881 - after his father, nicknamed the Liberator for the abolition of serfdom, was brutally murdered by revolutionaries in St. Petersburg. Alexander III ruled abruptly, unlike his predecessor, without flirting with the liberal public. The tsar responded with terror to terror, many revolutionaries were caught and hanged. Among others - Alexandra Ulyanova. His younger brother Vladimir, as we know, subsequently took revenge on the royal family.

The time of prohibitions, reaction, censorship and police arbitrariness - this is how contemporary oppositionists described the era of Alexander III (mainly from abroad, of course) and after them Soviet historians. And it was also the time of the war with the Turks in the Balkans for the liberation of the "Slavic brothers" (the one on which the brave intelligence officer Fandorin performed his feats), conquests in Central Asia, as well as various economic indulgences for the peasants, strengthening the army and overcoming budget disasters.

For our story, it is important that the busy king did not have so many free minutes for a family life. Almost the only (apocryphal) story about the relationship between father and son is associated with the beautiful ballerina Matilda Kshesinskaya. Allegedly, they told evil tongues, the king was upset and worried that the heir could not get a mistress in any way. And then one day harsh campaigners came to the chambers of his son (Alexander III was a simple, rude, harsh man, he led his friendship mainly with the military) and brought a gift from his father - a carpet. And on the carpet is the famous ballerina. Naked. So we met.

Nicholas's mother, Empress Maria Feodorovna (Princess Dagmara of Denmark) was little interested in Russian affairs. The heir grew up under the supervision of tutors - first an Englishman, then local. Received a decent education. Three European languages, and he spoke English almost better than Russian, an in-depth gymnasium course, then some university subjects.

Later - a pleasure trip to the mysterious countries of the East. In particular, to Japan. There was a problem with the heir. While walking, a samurai attacked the Tsarevich and struck the future Tsar on the head with a sword. In pre-revolutionary foreign brochures published by Russian revolutionaries, they wrote that the heir behaved impolitely in the church, and in one of the Bolsheviks - that a drunken Nikolai urinated on some statue. This is all propaganda lies. Nevertheless, there was one blow. Someone from the suite managed to reflect the second, but the sediment remained. And also - a scar, regular headaches and a dislike for the Land of the Rising Sun.

According to family tradition, the heir went through a kind of military practice in the guard. First - in the Preobrazhensky regiment, then - in the Life Guards Hussars. Here, too, is not without an anecdote. The hussars, in full accordance with the legend, were famous for their unrestrained drunkenness. At one time, when the regiment commander was Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich the Younger (grandson of Nicholas I, cousin of Nicholas II's father), the hussars even developed a whole ritual. Drank to the devil, they ran naked into the night - and howled, depicting a pack of wolves. And so - until the barman brought them a trough of vodka, from which the werewolves calmed down and went to sleep. So serving the heir is likely fun.

He served cheerfully, lived cheerfully, in the spring of 1894 he became engaged to Princess Alice of Hesse (she converted to Orthodoxy and became Alexandra Fedorovna). Marrying for love is a problem for crowned persons, but the future spouses somehow worked out right away, and in the future, in the course of their life together, they showed an unseen tenderness to each other.

Oh yes. Nikolai left Matilda Kshesinskaya immediately after the engagement. But the royal family liked the ballerina, then she was the mistress of two more grand dukes. She even gave birth to one.

In 1912, cadet V.P. Obninsky published in Berlin the book "The Last Autocrat", in which he collected, it seems, all the known slanderous rumors about the tsar. So, he reports that Nicholas tried to give up the reign, but his father, shortly before his death, forced him to sign the corresponding paper. However, no other historian confirms this rumor.

The last Russian tsar was definitely out of luck. Key events in his life - and in Russian history - did not portray him in the best light, and often without his obvious fault.

According to tradition, in honor of the coronation of the new emperor, a celebration was appointed in Moscow: on May 18, 1896, up to half a million people gathered on the Khodynskoye field (pitted with holes, bounded on one side by a ravine; in general, moderately convenient) for the festivities. The people were promised beer, honey, nuts, sweets, gift mugs with monograms and portraits of the new emperor and empress. As well as gingerbread and sausage.

The people began to gather the day before, and early in the morning someone shouted in the crowd that there would not be enough gifts for everyone. A wild crush began. The police were unable to contain the crowd. As a result, about two thousand people died, hundreds of crippled people ended up in hospitals.

But this is in the morning. In the afternoon, the police finally coped with the riots, the dead were taken away, the blood was sprinkled with sand, the emperor arrived on the field, the subjects were shouting the required "hurray." But, of course, they immediately started talking that the omen for the beginning of the reign was so-so. “Whoever began to reign with Khodynka will end up on the scaffold,” a mediocre but popular poet would write later. This is how a mediocre poet can turn out to be a prophet. The king is hardly personally responsible for the bad organization of the celebrations. But for many contemporaries, the words "Nikolai" and "Khodynka" somehow linked together.

In memory of the victims, Moscow students tried to stage a demonstration. They were dispersed, and the ringleaders were overfished. Nikolai showed that he was still the son of his father and did not intend to be liberal.

However, his intentions were generally vague. He visited, shall we say, European colleagues (the century of empires was not over yet) and tried to persuade the leaders of world powers to eternal peace. True, without enthusiasm and without much success, everyone in Europe understood even then that a big war was a matter of time. And no one understood how big it would be, this war. Nobody understood, nobody was afraid.

The tsar was clearly more interested in a quiet family life than in state affairs. One after another, daughters were born - Olga (even before the coronation), then Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia. The son was not, it caused concern. The dynasty needed an heir.

Cottage in Livadia, hunting. The king loved to shoot. The so-called "Diary of Nicholas II", all these dull, monotonous and endless "shot at crows", "killed a cat", "drank tea" - a fake; but the king fired at the innocent ravens and cats with enthusiasm.

Photo: Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky / Library of Congress

As mentioned above, the tsar was carried away by photography (and, by the way, in every possible way supported the famous Prokudin-Gorsky). And yet - he was one of the first in Europe to appreciate such a new thing as a car. I drove personally and had a hefty fleet of vehicles. Time passed unnoticed during pleasant activities. The tsar rode in a car in the parks, and Russia climbed into Asia.

Alexander III also understood that the empire would have to seriously fight in the East, and he sent his son on a cruise for nine months for a reason. In Japan, Nikolai, as we remember, did not like it. A military alliance with China against Japan is one of his first foreign policy affairs. Then there was the construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway (Chinese Eastern Railway), military bases in China, including the famous Port Arthur. And the dissatisfaction of Japan, and the severance of diplomatic relations in January 1904, and then - an attack on the Russian squadron.

Bird cherry quietly crept like a dream

And someone "Tsushima ..." said into the phone.

Hurry, Hurry! The term is running out!

"Varyag" and "Koreets" went east.

This is Anna Andreevna Akhmatova.

"Varyag" and "Korean", as everyone knows, died heroically in the Chemulpo Bay, but at first the reason for the Japanese success was seen solely in the cunning of the "yellow-faced devils". They were going to fight with the savages, the society was dominated by shapkozakidatelny mood. And then the tsar finally had an heir, Tsarevich Alexei.

Both the tsar, and the military, and many ordinary subjects, then experiencing patriotic enthusiasm, somehow did not notice that the Japanese savages were preparing for war in earnest, spending a lot of money, attracted the best foreign specialists and created an army and navy that were clearly more powerful than the Russians.

Failures followed one after another. The economy of the agrarian country did not keep up with the pace required to support the front. Communications were of no use - our Russia is too big and our roads are too bad. The Russian army at Mukden was defeated. A huge fleet crawled around half of the Earth from the Baltic to the Pacific Ocean, and then near the island of Tsushima was almost completely destroyed by the Japanese in a few hours. Port Arthur was handed over. Peace had to be concluded on humiliating terms. They gave, among other things, half of Sakhalin.

Embittered, crippled, having seen hunger, mediocrity, cowardice and theft of the command, the soldiers returned to Russia. Many soldiers.

And in Russia by that time a lot had happened. Bloody Sunday, for example, January 9, 1905. The workers, whose situation, naturally, worsened (after all, there was a war), decided to go to the tsar - to ask for bread and, oddly enough, political freedoms up to the people's representation. We met the demonstration with bullets, died - data vary - from 100 to 200 people. The workers became embittered. Nikolai was upset.

Then there was what is called the revolution of 1905 - riots in the army and cities, their bloody suppression and - as an attempt to reconcile the country - the Manifesto of October 17, which granted the Russians basic civil liberties and parliament - the State Duma. The Emperor dissolved the First Duma by his decree less than a year later. He didn't like the idea at all.

All these events did not add to the popularity of the sovereign. Among the intelligentsia, he seems to have no supporters at all. Konstantin Balmont, a rather nasty but very popular poet at that time, published abroad a book of poems with the pretentious title "Songs of the Struggle", which included, among other things, the poem "Our Tsar".

Our king is Mukden, our king is Tsushima,

Our king is a bloody stain

The stench of gunpowder and smoke

In which the mind is dark.

About the scaffold and Khodynka, cited above, - from the same place.

The time between the two wars is packed with events tight and dense. The Stolypin terror and the Stolypin land reform (“They need great upheavals, we need a great Russia”, - this beautiful phrase was quoted by V.V. Putin, R.A. Kadyrov, N.S. premiere.) Economic growth. First experiences of parliamentary work; Dumas that were always in conflict with the government and were dissolved by the tsar. Undercover fuss of the revolutionary parties destroying the empire - the Socialist-Revolutionaries, Mensheviks, Bolsheviks. Nationalist reaction, tacitly supported by the tsar Union of the Russian people, Jewish pogroms. The flourishing of the arts ...

The growth of influence at the court of Rasputin - a mad old man from Siberia, either a whip, or a holy fool, who finally managed to completely subordinate the Russian empress to his will: the Tsarevich was ill, Rasputin knew how to help him, and this worried the queen more than all the upheavals in the external the world.

To our proud capital

He comes in - God save me! -

Enchants the queen

Boundless Russia.

This is Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilev, the poem "Man" from the book "Fire".

It makes no sense, perhaps, to retell in detail the history of the First World War, which thundered in August 1914 (by the way, there is an interesting and unexpected document about the state of the country on the eve of the catastrophe: just in 1914, J. Grosvenor, an American who wrote for The National Geographic Magazine a long and enthusiastic article "Young Russia. A Land of Unlimited Opportunities" with a bunch of photographs; the country, according to the American, flourished).

In short, it all looked like a quote from quite recent newspapers: first, patriotic enthusiasm, then - failures at the front, the economy, unable to serve the front, bad roads.

And also - the tsar, who decided to personally lead the army in August 1915, and also - endless queues for bread in the capital and large cities, and right there - the rampant nouveau riche who "rose" on million-dollar military contracts, and still - many thousands of returning from front. Cripples and deserters. Those who have seen death up close, the dirt of gray Galicia, who have seen Europe ...

In addition, probably for the first time: the headquarters of the warring powers launched a large-scale information war, supplying the army and the rear of the enemy with the most terrible rumors, including about the august persons. And in millions of sheets of paper, stories spread throughout the country that our Tsar was a cowardly, feeble-minded drunkard, and his wife was Rasputin's mistress and a German spy.

All this, of course, was a lie, but what is important is this: in a world where the printed word was still believed and where ideas about the sacredness of autocratic power were still glowing, they were dealt a very strong blow. It was not German leaflets or Bolshevik newspapers that broke the monarchy, but their role should not be dismissed altogether.

Tellingly, the German monarchy did not survive the war either. The Austro-Hungarian Empire is over. In a world where the authorities have no secrets, where a journalist in a newspaper can gargle the sovereign as he wants, empires will not survive.

With all this in mind, it probably becomes clearer why, when the king abdicated, no one was particularly amazed. Except, perhaps, himself and his wife. At the end of February, his wife wrote to him that hooligans were operating in St. Petersburg (this is how she tried to comprehend the February Revolution), and he demanded to suppress the riots, no longer having loyal troops at hand. On March 2, 1917, Nikolai signed his abdication.

The provisional government sent the former tsar and his family to Tyumen, then to Tobolsk. The Tsar almost liked what was happening. It’s not so bad to be a private citizen and no longer be responsible for a huge, war-torn country. Then the Bolsheviks moved him to Yekaterinburg.

Then ... Everyone knows what happened next, in July 1918. Specific views of the Bolsheviks about political pragmatism. A brutal murder - of a king, queen, children, doctors, servants. Martyrdom turned the last autocrat into a holy martyr. The tsar's icons are now sold in any church shop, but with a portrait there is a certain difficulty.

A brave military man with a sleek beard, quiet, one might even say - kind (forgive killed cats) philistine, who loved his family and simple human joys, found himself - not without the intervention of chance - at the head of the largest country in the most terrible period of its history.

He seems to be hiding behind this story, there is little bright in him - not like in the events that passed by, touching him and his family, in the events that in the end ruined both him and the country, creating another. It is as if it does not exist, you cannot see it behind a series of catastrophes.

And the terrible death removes the questions that are so fond of asking in Russia: is the ruler to blame for the country's troubles? I'm sorry. Certainly. But no more than many others. And he paid dearly to atone for his guilt.

On May 6, 1868, a joyful event took place in the royal family: Emperor Alexander II had his first grandson! Cannons fired, fireworks thundered, the highest favors rained down. The father of the newborn was Tsarevich (heir to the throne) Alexander Alexandrovich, the future Emperor Alexander III, the mother was the Grand Duchess and Tsarevna Maria Feodorovna, nee Danish princess Dagmara. The baby was named Nikolai. He was destined to become the eighteenth and last emperor of the Romanov dynasty. For the rest of her life, his mother remembered the prophecy she heard at the time when she was expecting her first child. It was said that an old woman, a clairvoyant, predicted to her: "Your son will reign, everything will climb the mountain in order to gain wealth and great honor. Only if he does not climb the mountain itself, he will fall by the hand of a peasant."

Little Nicky was a healthy and mischievous child, so members of the imperial family sometimes had to tear the naughty heir by the ears. Together with his brothers George and Mikhail and sisters Olga and Ksenia, he grew up in a strict, almost Spartan environment. Father punished the mentors: "Teach well, do not make indulgences, ask in all severity, do not encourage laziness in particular ... I repeat that I do not need porcelain. I need normal, healthy Russian children. If they fight, please. But the prover will get the first whip. ".

They were trained for the role of ruler Nicholas from an early age. He received a versatile education from the best teachers and specialists of his time. The future emperor completed an eight-year general education course based on the classical gymnasium program, then a five-year course of higher education at the Faculty of Law of St. Petersburg University and the Academy of the General Staff. Nikolay was extremely assiduous and received fundamental knowledge in political economy, jurisprudence and military sciences. He was also taught horseback riding, fencing, drawing, music. He was fluent in French, English, German (he knew Danish worse), and wrote very competently in Russian. He was a passionate lover of books and, over the years, surprised his interlocutors with the breadth of his knowledge in the field of literature, history and archeology. From an early age, Nikolai had a great interest in military affairs and was, as they say, a born officer. His military career began at the age of seven, when his father enlisted the heir to the Life Guards Volyn Regiment and awarded him the military rank of ensign. He later served in the Preobrazhensky Life Guards Regiment, the most prestigious unit of the Imperial Guard. Having received the rank of colonel in 1892, Nikolai Alexandrovich remained in this rank until the end of his days.

From the age of 20, Nikolai was supposed to attend meetings of the State Council and the Committee of Ministers. And although these visits to the highest state bodies did not give him much pleasure, they significantly expanded the horizons of the future monarch. But he took to heart his appointment in 1893 as chairman of the Siberian Railway Committee, which was in charge of the construction of the world's longest railway. Nikolay quickly got up to speed and coped with his role quite successfully.

"The heir to the Tsarevich was very carried away by this undertaking ... - wrote in his memoirs S. Yu. Witte, who was then Minister of Railways," which, however, is not at all surprising, since Emperor Nicholas II is a man, undoubtedly, of a very quick mind and quick abilities; he generally grasps everything quickly and understands everything quickly. " Nicholas became Tsarevich in 1881, when his father ascended the throne under the name of Alexander III. This happened under tragic circumstances. Niki, 13, saw his reformer grandfather Alexander II die, crippled by a terrorist bomb. Twice Nikolai himself was on the verge of death. For the first time - in 1888, when the rails at the Borki station under the weight of the tsarist train parted, and the carriages fell down a slope. Then the crowned family survived only by a miracle. On another occasion, mortal danger lay in wait for the Tsarevich during a trip around the world undertaken by him at the request of his father in 1890-1891. Having visited Greece, Egypt, India, China and other countries, Nikolai, accompanied by relatives and retinue, arrived in Japan.

Here, in the city of Father, on April 29, he was unexpectedly attacked by a mentally ill policeman who was trying to hack him to death with a saber. But this time everything worked out: the saber only touched the head of the Tsarevich, without causing him serious harm. In a letter to his mother, Nikolai described this event as follows: “We drove out in jen rickshaws and turned into a narrow street with crowds on both sides. At that time I received a strong blow on the right side of my head, above my ear. the second time he swung a saber at me ... I just shouted: "What, what do you want?" And jumped over the jen-rickshaw onto the pavement. " The soldiers accompanying the crown prince hacked to death the attempted policeman with sabers. The poet Apollo Maikov dedicated a poem to this incident, which contained the following lines:

A regal youth, twice saved!

The twofolds of tender Rus are revealed

God's Providence is a shield over You!

It seemed that Providence twice saved the future emperor from death, only in order to hand him over, together with the whole family, into the hands of the regicides 20 years later.

On October 20, 1894, Alexander III, who suffered from an ironic kidney disease, died in Livadia (Crimea). His death was a deep shock for the 26-year-old Tsarevich, now Emperor Nicholas P. And it was not only that the son had lost his beloved father. Later, Nicholas II admitted that the very thought of the impending royal burden, heavy and inevitable, terrified him. “For me the worst happened, exactly what I was so afraid of for a century of life,” he wrote in his diary. Even three years after accession, he told his mother that only the "holy example of his father" did not allow him to "lose heart when sometimes moments of despair come." Shortly before his death, realizing that his days were numbered, Alexander III decided to speed up the marriage of the crown prince: after all, according to tradition, the new emperor should be married. The bride of Nicholas, the German princess Alice of Hesse-Darmstadt, the granddaughter of Queen Victoria of England, was urgently summoned to Livadia. She received a blessing from the dying king, and on October 21, in a small Livadian church, she was anointed, becoming the Orthodox Grand Duchess Alexandra Feodorovna.

A week after the funeral of Alexander III, a modest wedding ceremony of Nicholas II and Alexandra Feodorovna took place. This happened on November 14, on the birthday of the Tsar's mother, Empress Maria Feodorovna, when the Orthodox tradition made it possible to ease strict mourning. Nicholas II had been waiting for this marriage for several years, and now the great sorrow in his life was combined with great joy. In a letter to brother George, he wrote: “I cannot thank God enough for the treasure that He sent me in the form of a wife. ".

The accession to the throne of the new sovereign stirred up a wave of hopes in society for the liberalization of the country's life. On January 17, 1395, Nicholas received a deputation of the nobility, zemstvos and cities in the Anichkov Palace. The emperor was very worried, his voice trembled, he kept looking into the folder with the text of the speech. But the words that sounded in the hall were far from uncertainty: “I know that lately in some zemstvo meetings the voices of people carried away by senseless dreams about the participation of zemstvo representatives in the affairs of internal government have been heard. strength to the good of the people, I will protect the beginning of autocracy as firmly and unswervingly as my unforgettable late parent guarded it. " From excitement, Nikolai could not cope with his voice and uttered the last phrase very loudly, switching to a shout. Empress Alexandra Feodorovna still did not understand Russian well and, alarmed, asked the grand duchesses who were standing nearby: "What did he say?" “He explains to them that they are all idiots,” one of the august relatives replied calmly. The society very quickly became aware of the incident, they said that in the present text of the speech "baseless dreams" were written, but the king could not really read the words. It was also said that the leader of the nobility of the Tver province, Utkin, frightened by Nikolai's scream, dropped a golden tray of bread and salt from his hands. "This was considered a bad omen for the coming reign. Four months later, magnificent coronation celebrations took place in Moscow. Cathedral of the Kremlin, Nicholas II and his wife were married to the kingdom.

On these May holidays, the first great misfortune in the history of the last reign happened. It got the name - "Khodynki". On the night of May 18, at least half a million people gathered at the Khodynskoye field, where the exercises of the troops of the Moscow garrison were usually held. They expected a massive distribution of royal gifts, which seemed unusually rich. There was a rumor that money would also be distributed. In fact, the "coronation gift" consisted of a commemorative mug, a large gingerbread, sausage and sausage. At dawn, there was a tremendous crush, which eyewitnesses will later call the "end of the world." As a result, 1,282 people died and several hundred were injured.

This event shocked the king. Many advised him not to go to the ball given that evening by the French ambassador, Count of Montebello. But the tsar knew that this technique was supposed to demonstrate the strength of the political alliance between Russia and France. He did not want to hurt the French allies. And although the crowned spouses did not stay at the ball for long, public opinion did not forgive them for this step. The next day, the tsar and tsarina attended a memorial service for the dead, visited the Old Catherine Hospital, where the wounded were kept. The sovereign ordered to issue 1000 rubles for each family of the victims, to establish a special shelter for orphaned children, and to take all expenses for the funeral at his expense. But the people already called the tsar an indifferent, heartless man. In the illegal revolutionary press, Nicholas II received the nickname "Tsar Khodynsky".

On November 1, 1905, Emperor Nicholas II wrote in his diary: "We met the man of God - Gregory from the Tobolsk province." On that day, Nicholas II did not yet know that 12 years later, many would associate the fall of the Russian autocracy with the name of this man, that the presence of this man at court would be evidence of the political and moral degradation of the tsarist power.

Grigory Efimovich Rasputin was born in 1864 or 1865 (the exact date is unknown) in the village of Pokrovskoye, Tobolsk province. He came from a peasant family of average income. It seemed that he was destined for the usual fate of a peasant from a remote village. Rasputin started drinking early, at the age of 15. After getting married at the age of 20, his drunkenness only intensified. Then Rasputin began to steal, for which he was repeatedly beaten by his fellow villagers. And when a criminal case was opened against him in the Pokrovsky volost court, Gregory, without waiting for the denouement, went to the Perm province to the Verkhotursky monastery. This three-month pilgrimage marked the beginning of a new period in Rasputin's life. He returned home greatly changed: he stopped drinking and smoking, he stopped eating meat. For several years Rasputin, forgetting about family and household, visited many monasteries, even reaching the sacred Greek Mount Athos. In his native village, Rasputin began to preach in the prayer house he had equipped. The newly-minted "elder taught his parishioners moral liberation and healing of the soul through committing the sin of adultery: if you do not sin, you will not repent, if you do not repent, you will not be saved. As a rule, such" services "ended in open orgies.

The fame of the new preacher grew and strengthened, and he willingly used the benefits of his fame. In 1904 he ended up in St. Petersburg, was introduced by Bishop Theophan of Yamburg to the aristocratic salons, where he successfully continued his sermons. The seeds of Rasputinism fell into fertile soil. The Russian capital was in those years in a severe moral crisis. The fascination with the other world became widespread, and sexual promiscuity reached an extreme scale. In a very short time, Rasputin acquired many admirers, ranging from noble ladies and girls to ordinary prostitutes.

Many of them found a way out for their emotions in "communication" with Rasputin, others tried to solve money problems with his help. But there were also those who believed in the holiness of the "elder". It was thanks to such fans that Rasputin ended up at the court of the emperor.

Rasputin was far from the first in a series of "prophets", "righteous", "seers" and other rogues who at various times appeared in the environment of Nicholas P. Even before him, fortunetellers Papus and Philip, various holy fools and other dark personalities entered the royal family ...

Why did the royal couple allow themselves to communicate with such people? Such moods were inherent in the empress, who, since childhood, was interested in everything unusual and mysterious. Over time, this character trait has become even more entrenched in her. Frequent childbirth, the tense expectation of the birth of a male heir to the throne, and then his serious illness brought Alexandra Feodorovna to religious exaltation. The constant fear for the life of her son, who was sick with hemophilia (incoagulability of blood), forced her to seek protection in religion and even turn to outright charlatans.

It was on these feelings of the empress that Rasputin skillfully played. Rasputin's remarkable hypnotic abilities helped him gain a foothold at court, primarily as a healer. More than once he managed to "speak" - blood to the heir, to alleviate the empress's migraine. Very soon Rasputin inspired Alexandra Fyodorovna, and through her and Nicholas II, that while he was at court, nothing bad would happen to the imperial family. Moreover, in the first years of their communication with Rasputin, the tsar and tsarina did not hesitate to offer their entourage to use the healing services of the "elder". There is a known case when P.A.Stolypin, a few days after the explosion on Aptekarsky Island, found Rasputin praying at the bedside of his seriously wounded daughter. The Empress herself recommended that Rasputin be invited to Stolypin's wife.

Rasputin was able to gain a foothold at court largely thanks to A.A. Vyrubova, the Empress's maid of honor and her closest friend. At Vyrubova's dacha, located not far from the Tsarskoye Selo Alexander Palace, the Empress and Nicholas II met with Rasputin. A devoted fan of Rasputin, Vyrubova served as a kind of link between him and the royal family. Rasputin's closeness to the imperial family quickly became public, which the "elder" subtly took advantage of. Rasputin refused to accept any money from the Tsar and Tsarina. This "loss" he more than made up for in high society salons, where he accepted offerings from aristocrats who were seeking closeness to the tsar, bankers and industrialists who defended their interests, and others hungry for the patronage of the supreme power. By the highest order, the Police Department assigned guards to Rasputin. However, since 1907, when the "elder" became more than a "preacher" and "healer", he was under surveillance - surveillance. The spies' observation diaries impartially recorded Rasputin's pastime: carousing in restaurants, going to the bathhouse in the company of women, trips to gypsies, etc. Since 1910, reports of Rasputin's riotous behavior began to appear in newspapers. The scandalous notoriety of the "elder" acquired rampant proportions, compromising the royal family.

At the beginning of 1911, P. A. Stolypin and the Chief Prosecutor of the Holy Synod S. M. Lukyanov presented a detailed report to Nicholas II, debunking the sanctity of the "elder" and painting on the basis of documents of his adventures. The tsar's reaction was very sharp, but, having received help from the empress, Rasputin not only survived, but also strengthened his position even more. For the first time, the "friend" (as Rasputin called Alexandra Fedorovna) had a direct impact on the appointment of a statesman: the opponent of the "elder" Lukyanov was dismissed, and B. K. Sabler, who was loyal to Rasputin, was appointed in his place. In March 1912, the chairman of the State Duma, M.V. Rodzianko, launched an attack on Rasputin. Having had a preliminary conversation with the mother of Nicholas II, Maria Feodorovna, he, with documents in his hands at an audience with the emperor, painted a terrible picture of the depravity of the tsar's entourage and emphasized the enormous role that he played in the loss of his reputation by the supreme power. But neither Rodzianko's admonitions, nor the subsequent conversations between the tsar and his mother, his uncle, Grand Duke Nikolai Mikhailovich, who was considered the keeper of traditions in the imperial family, nor the efforts of the Empress's sister, Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna, shook the position of the "elder." It was at this time that the phrase of Nicholas II refers: "Better one Rasputin than ten scandals a day." Sincerely loving his wife, Nikolai could no longer resist her influence and in relation to Rasputin invariably took the side of the empress. For the third time, Rasputin's position at court was shaken in June - August 1915 after a noisy revelry in the Moscow restaurant "Yar", where, after drinking heavily, the "holy elder" while missing out on the royal family. As it was later reported to the assistant minister of internal affairs VF Dzhunkovsky, "Rasputin's behavior took on a completely ugly character of some kind of sexual psychopathy ...". It was about this scandal that Dzhunkovsky reported in detail to Nikolai P. The emperor was extremely irritated by the behavior of the "friend", agreed with the general's requests to send the "elder" to his homeland, but ... a few days later he wrote to the Minister of Internal Affairs: "I insist on the immediate expulsion of General Dzhunkovsky." ...

This was the last serious threat to Rasputin's position at court. From that time until December 1916, Rasputin's influence reached its climax. Until now, Rasputin was interested only in church affairs. The incident with Dzhunkovsky showed that civil authorities can also be dangerous for the "sanctity" of the tsarist "lamp-lamp". From now on, Rasputin seeks to control the official government, and primarily the key posts of the ministers of the interior and justice.

The first victim of Rasputin was the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich. Once it was the prince's wife, with his direct participation, who brought Rasputin into the palace. Having mastered the royal chambers, Rasputin managed to spoil the relationship between the tsar and the grand duke, becoming the latter's worst enemy. After the start of the war, when Nikolai Nikolaevich, who was popular among the troops, was appointed the supreme commander-in-chief, Rasputin intended to visit the Supreme Headquarters in Baranovichi. In response, he received a laconic telegram: "Come - I'll hang!" Moreover, in the summer of 1915 Rasputin found himself "on a hot frying pan" when, on the direct advice of the Grand Duke Nicholas II, he dismissed four of the most reactionary ministers, including Sabler, whose place was taken by the ardent and open enemy of Rasputin A. D. Samarin - Moscow provincial leader of the nobility.

Rasputin managed to convince the empress that the stay of Nikolai Nikolaevich at the head of the army threatened the tsar with a coup, after which the throne would pass to the great prince respected by the military. In the end, Nicholas II himself took the post of supreme commander, and the Grand Duke was sent to the secondary Caucasian front.

Many Russian historians believe that this moment became a key one in the crisis of the supreme power. Far from Petersburg, the emperor finally lost control of the executive branch. Rasputin acquired unlimited influence over the empress and was able to dictate the personnel policy of the autocracy.

Rasputin's political tastes and passions are shown by the appointment, under his patronage, of the Minister of Internal Affairs A. N. Khvostov, the former governor of Nizhny Novgorod, the leader of the conservatives and monarchists in the State Duma, who has long been nicknamed the Nightingale the Robber. This enormous "man without detention centers", as he was called in the Duma, eventually sought to occupy the highest bureaucratic post - the chairman of the Council of Ministers. SP Beletsky, known among his family as an exemplary family man, and among his acquaintances as the organizer of "Athenian evenings", erotic shows in the ancient Greek style, became Khvostov's companion (deputy).

Khvostov, having become a minister, carefully concealed Rasputin's involvement in his appointment. But the "elder", wanting to keep Khvostov in his hands, advertised his role in his career in every possible way. In response, Khvostov decided ... to kill Rasputin. However, Vyrubova became aware of his attempts. After a huge scandal, Khvostov was dismissed. The rest of the appointments at the behest of Rasputin were no less scandalous, especially two of them: B.V. time even overshadowed the notoriousness of the "elder" himself, became deputy chairman. In many ways, these and other appointments of random people to responsible positions upset the country's internal economy, contributing directly or indirectly to the rapid fall of the monarchical power.

Both the tsar and the empress were well aware of the "elder" lifestyle and the very specific aroma of his "holiness". But, in spite of everything, they continued to listen to the "friend". The fact is that Nicholas II, Alexandra Feodorovna, Vyrubova and Rasputin constituted a kind of circle of like-minded people. Rasputin never proposed candidates that did not completely suit the Tsar and Tsarina. He never recommended anything without consulting Vyrubova, who gradually persuaded the queen, after which Rasputin spoke himself.

The tragedy of the moment was that the representative of the Romanov dynasty who was in power and his wife were worthy of just such a favorite as Rasputin. Rasputin only illustrated the complete lack of logic in governing the country in the last pre-revolutionary years. "What is this, stupidity or treason?" - asked PN Milyukov after each phrase of his speech in the Duma on November 1, 1916. In reality, it was an elementary inability to rule. On the night of December 17, 1916, Rasputin was secretly killed by representatives of the St. Petersburg aristocracy, who hoped to save the tsar from destructive influences and save the country from collapse. This murder became a kind of parody of the palace coups of the 18th century: the same solemn entourage, the same, albeit futile, mystery, the same nobility of the conspirators. But nothing could change this step. The tsar's policy remained the same, there was no improvement in the country's position. The Russian empire moved uncontrollably towards its downfall.

The royal "cross" turned out to be difficult for Nicholas P. The emperor never doubted that he was placed in his highest office by Divine Providence, in order to rule for the strengthening and prosperity of the state. From a young age he was brought up in the conviction that Russia and the autocracy are inseparable things. In the questionnaire of the first All-Russian population census in 1897, when asked about his occupation, the emperor wrote: "Master of the Russian Land." He fully shared the point of view of the famous conservative Prince VP Meshchersky, who believed that "the end of autocracy is the end of Russia."

Meanwhile, there was almost no "autocracy" in the appearance and character of the last sovereign. He never raised his voice, was polite to ministers and generals. Those who knew him closely spoke of him as a "kind", "extremely educated" and "charming man. One of the main reformers of this reign, S. Yu. Witte (see the article" Sergei Witte "; wrote about what was hidden behind charm and the courtesy of the emperor: "... Emperor Nicholas II, who ascended the throne quite unexpectedly, representing a kind person, far from stupid, but shallow, weak-willed, in the end a good person who did not inherit all the qualities of his mother and partly of his ancestors (Paul) and very few qualities of a father, was not created to be an emperor in general, but an unlimited emperor of an empire like Russia, in particular. His main qualities are courtesy when he wanted it, cunning and complete spinelessness and weakness. " AA Mosolov, head of the Chancellery of the Ministry of the Imperial Court, wrote that “Nicholas II was by nature very shy, did not like to argue partly out of fear that he might be proved the equality of his views or to convince others of this ... The king was not only polite, but even considerate and affectionate with all those who came into contact with him. He never paid attention to the age, position, or social status of the person with whom he spoke. Both for the minister and for the last valet, the tsar always had an even and polite manner. "Nicholas II was never distinguished by his love of power and looked at power as a heavy duty. Contemporaries were surprised by the amazing self-control of Nicholas II, the ability to control himself under any circumstances. His philosophical calmness, mainly associated with the peculiarities of his worldview, seemed to many to be “terrible, tragic indifference.” God, Russia and family were the most important life values of the last emperor. He was a deeply religious person, and this explains a lot in his fate as a ruler. From childhood he strictly observed all Orthodox rituals, knew church customs and traditions well. Faith filled the tsar's life with deep content, freed him from the slavery of earthly circumstances, helped to endure numerous upheavals and adversity. ”In time, the crown bearer became a fatalist, who believed that everything is in the hands of the Lord and that one must submit with humility to His holy will. " Not long before the fall of the monarchy, when the approach of the denouement was felt by everyone, he recalled the fate of the biblical Job, whom God, wanting to test, deprived children, health, wealth. Responding to the complaints of relatives about the state of affairs in the country, Nicholas II said: "Everything is God's will. I was born on May 6, on the day of commemoration of the long-suffering Job. I am ready to accept my fate."

The second most important value in the life of the last tsar was Russia. From a young age, Nikolai Alexandrovich was convinced that the imperial power is a blessing for the country. Shortly before the start of the revolution of 1905-1907. he said: "I will never, in no way agree to a representative form of government, because I consider it harmful for the people entrusted to me by God." The monarch, according to Nicholas, was a living personification of law, justice, order, supreme power and traditions. He perceived the departure from the principles of power inherited by him as a betrayal of the interests of Russia, as an outrage over the sacred foundations bequeathed by his ancestors. "The autocratic power bequeathed to me by my ancestors, I must pass safely to my son," Nikolai believed. He was always keenly interested in the country's past, and in Russian history Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, nicknamed the Quietest, aroused his special sympathy. The time of his reign seemed to Nicholas II the golden age of Russia. The last emperor would gladly fail his reign so that he could be awarded the same nickname.

And yet Nicholas was aware of the fact that the autocracy at the beginning of the XX century. already different in comparison with the era of Aleksey Mikhailovich. He could not ignore the demands of the times, but he was convinced that any drastic changes in the social life of Russia are fraught with unpredictable consequences, disastrous for the country. So, perfectly aware of the trouble of the multimillion-strong mass of the peasantry, suffering from landlessness, he categorically objected to the forcible seizure of land from the landlords and defended the inviolability of the principle of private property. The king always strived to ensure that innovations were implemented gradually, taking into account traditions and past experience. This explains his desire to leave the implementation of reforms to his ministers, himself remaining in the shadows. The emperor supported the policy of industrialization of the country pursued by the Minister of Finance S. Yu. Witte, although this course was met with hostility in various circles of society. The same thing happened with the program of agrarian reorganization of PA Stolypin: only reliance on the will of the monarch allowed the prime minister to carry out the planned transformations.

The events of the first Russian revolution and the forced publication of the Manifesto on October 17, 1905 were perceived by Nicholas as a deep personal tragedy. The emperor knew about the upcoming procession of workers to the Winter Palace on January 3, 1905. He told his family that he wanted to go out to the demonstrators and accept their petition, but the family united against such a step, calling it "madness." The tsar could easily be killed both by the terrorists who had crowded into the ranks of the workers, and the crowd itself, whose actions were unpredictable. The gentle, influenced Nikolai agreed and spent January 5 at Tsarskoe Selo near Petrograd. The news from the capital horrified the sovereign. “It's a hard day!” He wrote in his diary, “There are serious riots in St. Petersburg ... The troops had to shoot, in different parts of the city there were many killed and wounded. Lord, how painful and hard it is!”

By signing the Manifesto on the Granting of Civil Liberties to Subjects, Nikolai violated the political principles that he considered sacred. He felt betrayed. In his memoirs, S. Yu. Witte wrote about this: “During all the October days, the sovereign seemed completely calm. I don’t think he was afraid, but he was completely confused, otherwise, with his political tastes, of course, he would not have gone on the constitution. I think that the sovereign in those days was looking for support in strength, but did not find anyone from among the admirers of strength - everyone was afraid. " When Prime Minister P. A. Stolypin in 1907 informed the emperor that "the revolution was generally suppressed," he heard a stunned answer: "I do not understand what kind of revolution you are talking about. True, there were riots, but this not a revolution ... And unrest, I think, would have been impossible if more energetic and courageous people were in power. " These words Nicholas II with good reason could have attributed to himself.

The emperor did not take full responsibility neither for reforms, nor in military leadership, nor in suppressing unrest.

An atmosphere of harmony, love and peace reigned in the family of the emperor. Here Nicholas always rested with his soul and drew strength to fulfill his duties. On April 8, 1915, on the eve of the next anniversary of the engagement, Alexandra Feodorovna wrote to her husband: "Dear, how many difficult trials we have endured over all these years, but it was always warm and sunny in our native nest."

Having lived a life full of shocks, Nicholas II and his wife Alexandra Feodorovna retained to the end a lovingly enthusiastic attitude towards each other. Their honeymoon lasted over 23 years. Few people guessed about the depth of this feeling at that time. Only in the mid-1920s, when three voluminous volumes of correspondence between the tsar and the tsarina (about 700 letters) were published in Russia, was the amazing story of their boundless and all-consuming love for each other revealed. 20 years after the wedding, Nicholas wrote in his diary: "It is hard to believe that today is the 20th anniversary of our wedding. The Lord blessed us with rare family happiness; if only we could be worthy of His great mercy during the rest of our lives."

Five children were born in the royal family: Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia and Tsarevich Alexei. Daughters were born one after another. In the hope of the appearance of an heir, the imperial couple began to get carried away with religion, was the initiator of the canonization of Seraphim of Sarov. Piety supplemented interest in spiritualism and the occult. Various soothsayers and holy fools began to appear at the court. Finally, in July 1904, a son, Alexei, was born. But the parental joy turned out to be darkened - the child was diagnosed with an incurable hereditary disease hemophilia.

Pierre Gilliard, teacher of the tsar's daughters, recalled: "What was best for these four sisters was their simplicity, naturalness, sincerity and unaccountable kindness." An entry in the diary of the priest Afanasy Belyaev, who in Easter 1917 had a chance to confess the arrested members of the royal family, is also characteristic. "May God grant that all children are morally as tall as the children of a former boyfriend. Such gentleness, humility, obedience to the parental will, unconditional devotion to the will of God, purity in thoughts and complete ignorance of earthly dirt, passionate and sinful, amazed me." - he wrote.

"An unforgettable great day for us, on which the mercy of God visited us so clearly. At 12 pm, Alix had a son, who was named Alexei during prayer." So Emperor Nicholas II wrote in his diary on July 30, 1904.

Alexey was the fifth child of Nicholas II and Alexandra Feodorovna. Not only the Romanov family, but the whole of Russia, waited for his birth for many years, because the significance of this boy for the country was enormous. Alexei became the first (and only) son of the emperor, which means - the Heir to the Tsarevich, as the heir to the throne in Russia was officially called. His birth determined who, in the event of the death of Nicholas II, would have to lead a huge power. After Nikolai's accession to the throne, Grand Duke George Alexandrovich, the king's brother, was declared heir. When Georgy Alexandrovich died of tuberculosis in 1899, the tsar's younger brother, Mikhail, became the heir. And now, after the birth of Alexei, it became clear that the direct line of succession to the Russian throne would not be stopped.

The life of this boy from birth was subordinated to one thing - the future reign. Even the name of the heir was given by the parents with meaning - in memory of the idol Nicholas II, the "quietest" Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich. Immediately after birth, little Alexei was included in the lists of twelve guards military units. By the time of his majority, the heir should have already had a fairly high military rank and be listed as the commander of one of the battalions of any guards regiment - in accordance with tradition, the Russian emperor must have been a military man. The newborn was also entitled to all other grand-princely privileges: own land, efficient staff of servants, pay, etc.

At first, nothing foreshadowed trouble for Alexei and his parents. But once already three-year-old Alexei fell during a walk and badly bruised his leg. A common bruise, which many children do not pay attention to, has grown to alarming proportions, the heir's temperature has risen sharply. The verdict of the doctors who examined the boy was terrible: Alexey was sick with a serious illness - hemophilia. Hemophilia, a disease in which there is no blood clotting, threatened the heir to the Russian throne with dire consequences. Now every bruise or cut could become fatal for a child. Moreover, it was well known that the life expectancy of patients with hemophilia is extremely short.

From now on, the entire routine of the heir's life was subordinated to one main goal - to protect him from the slightest danger. A lively and agile boy, Alexei was now forced to forget about active games. With him on walks was always attached to the "uncle" - the sailor Derevenko from the imperial yacht "Standart". And nevertheless, new attacks of the disease could not be avoided. One of the most severe attacks of the disease occurred in the fall of 1912. During a boat trip, Alexei, wanting to jump ashore, accidentally hit the side. A few days later he could no longer walk: the sailor assigned to him carried him in his arms. The hemorrhage turned into a huge tumor that covered half of the boy's leg. The temperature rose sharply, reaching almost 40 degrees on some days. The largest Russian doctors of that time, Professors Rauchfus and Fedorov, were urgently called to the patient. However, they also failed to achieve a radical improvement in the child's health. The situation was so threatening that it was decided to start publishing official bulletins on the health of the heir in the press. Alexei's serious illness continued throughout the fall and winter, and only by the summer of 1913 was he able to walk on his own again.

Alexey owed his serious illness to his mother. Hemophilia is a hereditary disease that affects only men, but is transmitted through the female line. Alexandra Feodorovna inherited a serious illness from her grandmother, Queen Victoria of England, whose broad kinship led to the fact that in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century, hemophilia began to be called the disease of kings. Many of the descendants of the famous English queen suffered from a serious illness. So, the brother of Alexandra Feodorovna died of hemophilia.

Now the disease has struck the only heir to the Russian throne. However, despite a serious illness, Alexei was prepared for the fact that he would one day have to ascend to the Russian throne. Like all his closest relatives, the boy was educated at home. Pierre Gilliard, a Swiss, was invited to be his teacher, teaching the boy languages. The most famous Russian scientists of that time were preparing to teach the heir. But illness and war prevented Alexey from studying normally. With the outbreak of hostilities, the boy often visited the army with his father, and after Nicholas II took over the high command, he was often with him at Headquarters. The February revolution found Alexei with his mother and sisters in Tsarskoe Selo. Together with his family, he was arrested, together with her he was sent to the east of the country. Together with all his relatives, he was killed by the Bolsheviks in Yekaterinburg.

At the end of the 19th century, by the beginning of the reign of Nicholas II, the Romanov surname numbered about two dozen members. Grand dukes and princesses, uncles and aunts of the tsar, his brothers and sisters, nephews and nieces - all of them were quite prominent figures in the life of the country. Many of the grand dukes held responsible government positions, took part in the command of the army and navy, the activities of government institutions and scientific organizations. Some of them had a significant influence on the tsar, allowed themselves, especially in the first years of the reign of Nicholas II, to interfere in his affairs. However, most of the grand dukes had a reputation for being incompetent leaders, unfit for serious work.

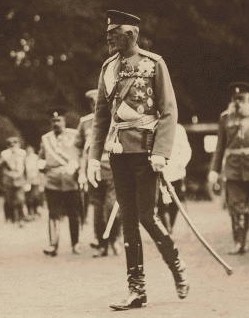

However, there was one among the great dukes who had a popularity almost equal to the popularity of the king himself. This is the Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich, the grandson of Emperor Nicholas I, the son of the Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich, the elder, who commanded the Russian troops during the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-1878.

Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich Jr. was born in 1856. He studied at the Nikolaev Military Engineering School, and in 1876 graduated from the Nikolaev Military Academy with a silver medal, and his name was on the marble plaque of honor of this most prestigious military educational institution. The Grand Duke also took part in the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-78.

In 1895, Nikolai Nikolaevich was appointed inspector general of the cavalry, effectively becoming the commander of all cavalry units. At this time, Nikolai Nikolaevich gained considerable popularity among the guard officers. Tall (his height was 195 cm), fit, energetic, with noble gray hair on the temples, the Grand Duke was the outer embodiment of the ideal of an officer. And the overwhelming energy of the Grand Duke only contributed to the increase in his popularity.

Nikolai Nikolaevich is known for his adherence to principles and strictness not only in relation to soldiers, but also to officers. Bypassing the troops with checks, he achieved their excellent training, ruthlessly punished negligent officers, seeking from them attention to the needs of the soldiers. For this, he became famous among the lower ranks, quickly gaining popularity in the army no less than the popularity of the king himself. Possessing a courageous appearance and a loud voice, Nikolai Nikolaevich personified the strength of the tsarist power for the soldiers.

After military setbacks during the Russo-Japanese War, the Grand Duke was appointed commander-in-chief of the Guard and the Petersburg Military District. He very quickly managed to extinguish the fire of discontent with the mediocre leadership of the army in the guards units. Largely thanks to Nikolai Nikolaevich, the troops of the guard, without hesitation, dealt with the uprising in Moscow in December 1905. During the revolution of 1905, the influence of the Grand Duke increased enormously. Commanding the capital's military district and the guard, he became one of the key figures in the fight against the revolutionary movement. The position in the capital depended on his decisiveness, and, consequently, the ability of the state apparatus of the empire to govern a huge country. Nikolai Nikolaevich used all his influence in order to convince the tsar to sign the famous manifesto on October 17. When the then Chairman of the Council of Ministers S.Yu. Witte presented the draft of the manifesto to the tsar for signing, Nikolai Nikolaevich did not leave the emperor a single step until the manifesto was signed. The Grand Duke, according to some courtiers, even threatened the tsar to shoot himself in his chambers if he did not sign a document that would save the monarchy. And although this information can hardly be considered true, such an act would be quite typical for the Grand Duke.

Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich continued to be one of the main leaders of the Russian army in subsequent years. In 1905-1908. he chaired the Council of State Defense, which was responsible for planning the combat training of troops. His influence on the emperor was just as great, although after the signing of the manifesto on October 17, Nicholas II treated his cousin uncle without the tenderness that was characteristic of their relationship before.

In 1912, Minister of War V.A. Sukhomlinov, one of those whom the Grand Duke could not stand, prepared a big war game - staff maneuvers, in which all commanders of military districts were to take part. The king himself was in charge of the game. Nikolai Nikolaevich, who hated Sukhomlinov, spoke with the emperor half an hour before the maneuvers began, and ... the war game, which had been preparing for several months, was canceled. The Minister of War had to resign, which, however, the tsar did not accept.

When the First World War began, Nicholas II had no doubts about the candidacy of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief. They were appointed by the Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich. The Grand Duke did not have any special military leadership talents, but it was thanks to him that the Russian army emerged with honor from the hardest trials of the first year of the war. Nikolai Nikolaevich knew how to competently select his officers. The supreme commander-in-chief gathered competent and experienced generals at the headquarters. After listening to them, he knew how to make the most correct decision, for which he alone had to bear responsibility now. True, Nikolai Nikolayevich did not stay at the head of the Russian army for long: a year later, on August 23, 1915, Nikolai II took over the supreme command, and "Nikolasha" was appointed commander of the Caucasian front. Removing Nikolai Nikolaevich from the command of the army, the tsar strove to get rid of his relative, who had acquired unprecedented popularity. In the Petrograd salons, they started talking about the fact that "Nikolasha" could replace his not very popular nephew on the throne.

A.I. Guchkov recalled that many politicians at that time believed that it was Nikolai Nikolaevich who, with his authority, was able to prevent the collapse of the monarchy in Russia. Political gossips called Nikolai Nikolayevich a possible successor to Nicholas II in the event of his voluntary or forcible removal from power.

Be that as it may, but Nikolai Nikolaevich has established himself in these years both as a successful commander and as an intelligent politician. The troops of the Caucasian Front led by him successfully advanced in Turkey, and the rumors associated with his name remained rumors: the Grand Duke did not miss an opportunity to assure the Tsar of his loyalty.

When the monarchy in Russia was overthrown and Nicholas II abdicated, it was Nikolai Nikolaevich who was appointed by the Provisional Government as the Supreme Commander-in-Chief. True, he stayed with them for only a few weeks, after which, due to belonging to the imperial family, he was again removed from command.

Nikolai Nikolayevich left for Crimea, where, together with some other representatives of the Romanov family, he settled in Dyulber. As it turned out later, leaving Petrograd saved their lives. When the Civil War began in Russia, Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich found himself in the territory occupied by the White Army. Remembering the immense popularity of the Grand Duke, General A.I. Denikin turned to him with a proposal to lead the fight against the Bolsheviks, but Nikolai Nikolaevich refused to participate in the Civil War and in 1919 left Crimea, going to France. He settled in the south of France, and in 1923 he moved to the town of Chouigny near Paris. In December 1924 he received from Baron P.N. Wrangel, the leadership of all foreign Russian military organizations, which, with his participation, were united into the Russian All-Military Union (ROVS). During these years, Nikolai Nikolaevich fought with his nephew, Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich for the right to be the locum tenens of the Russian throne.

Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich died in 1929.

The decisive role in the fate of the country and the monarchy was played by the First World War, in which Russia sided with England and France against the Austro-German bloc. Nicholas II did not want Russia to enter the war. Russian Foreign Minister S. D. Sazonov later recalled his conversation with the emperor on the eve of the announcement of mobilization in the country: “The Emperor was silent. Then he told me in a voice that sounded deeply agitated:“ This means condemning hundreds of thousands of Russian people to death. How not to stop at such a decision? "

The outbreak of the war caused a rise in patriotic feelings, which united representatives of various social forces. This time became a kind of finest hour of the last emperor, who turned into a symbol of hope for a quick and complete victory. On July 20, 1914, on the day of the declaration of war, crowds of people with portraits of the Tsar flooded the streets of St. Petersburg. A deputation from the Duma came to the Winter Palace with an expression of support. One of its representatives, Vasily Shulgin, talked about this event: “Constrained so that he could reach out to the front rows, the sovereign stood. This was the only time when I saw excitement on his enlightened face. "What was this crowd shouting not of young men, but of elderly people? They shouted:" Lead us, sir! "

But the first successes of Russian weapons in East Prussia and Galicia proved to be fragile. In the summer of 1915, under the powerful onslaught of the enemy, Russian troops left Poland, Lithuania, Volyn, Galicia. The war gradually became protracted and was far from over. Upon learning of the capture of Warsaw by the enemy, the emperor exclaimed with anger: "This cannot continue, I cannot all sit here and watch as my army is being crushed; I see mistakes - and must be silent!" Wishing to raise the morale of the army, Nicholas II took over the duties of the Commander-in-Chief in August 1915, replacing Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich in this post. As SD Sazonov recalled, "in Tsarskoe Selo, a mystical belief was expressed that the mere appearance of the Tsar at the head of the troops should have changed the state of affairs at the front." He now spent most of his time at the Supreme Command Headquarters in Mogilev. Time worked against the Romanovs. The protracted war exacerbated old problems and constantly gave birth to new ones. Failures at the front caused discontent, which erupted in critical speeches of newspapers, in speeches of the State Duma deputies. The unfavorable course of affairs was associated with the poor leadership of the country. Once, talking with the chairman of the Duma, MV Rodzianko, about the situation in Russia, Nikolai almost groaned: "Have I really tried for twenty-two years to make everything better, and have been wrong for twenty-two years ?!"

In August 1915, several Duma and other social groups united into the so-called "Progressive Bloc", the center of which was the Cadet Party. Their most important political demand was the creation of a ministry responsible to the Duma - a "cabinet of confidence." At the same time, it was assumed that leading posts in it would be occupied by persons from the Duma circles and the leadership of a number of social and political organizations. For Nicholas II, this step would mean the beginning of the end of the autocracy. On the other hand, the tsar understood the inevitability of serious reforms of state administration, but considered it impossible to carry them out in a war. A dull fermentation intensified in society. Some confidently said that treason was nesting in the government, that high-ranking officials were cooperating with the enemy. Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna was often named among these "agents of Germany". No evidence has ever been cited to support this. But public opinion did not need proof and once and for all passed its merciless verdict, which played a large role in the growth of anti-Romanian sentiments. These rumors also spread to the front, where millions of soldiers, mainly former peasants, suffered and died for goals that were known only to their superiors. Conversations about the betrayal of high dignitaries here aroused indignation and enmity towards all the "capital's well-fed khlyshchi". This hatred was skillfully fueled by left-wing political groups, primarily the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Bolsheviks, who advocated the overthrow of the "Romanov clique."

By the beginning of 1917, the situation in the country had become extremely tense. At the end of February, unrest began in Petrograd, caused by interruptions in the supply of food to the capital. These riots, not meeting serious opposition from the authorities, a few days later escalated into mass protests against the government, against the dynasty. The tsar learned about these events in Mogilev. “Riots began in Petrograd,” the tsar wrote in his diary on February 27, “unfortunately, the troops began to take part in them as well. A disgusting feeling of being so far away and receiving fragmentary bad news!” Initially, the tsar wanted to restore order in Petrograd with the help of troops, but was unable to get to the capital. On March 1, he wrote in his diary: "Shame and shame! It was not possible to get to Tsarskoye. But thoughts and feelings are there all the time!"

Some high-ranking military officials, members of the imperial retinue and representatives of public organizations convinced the emperor that a change of government was required to pacify the country, his abdication from the throne was necessary. After much deliberation and hesitation, Nicholas II decided to renounce the throne. The choice of a successor was also difficult for the emperor. He asked his doctor to frankly answer the question of whether Tsarevich Alexei could be cured of a congenital blood disease. The doctor just shook his head - the boy's illness was fatal. “If God has already decided so, I will not part her as my poor child,” Nikolai said. He abdicated power. Nikolai II sent a telegram to the Chairman of the State Duma M. V. Rodzianko: "There is no sacrifice that I would not make for the sake of the real good and for the salvation of my mother Russia. Therefore, I am ready to abdicate the throne in favor of my son, so that remained with me until adulthood, with the regency of my brother, Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich. " Then the brother of the tsar, Mikhail Alexandrovich, was elected heir to the throne. On March 2, 1917, on his way to Petrograd, at the small station Dno near Pskov, in the saloon of the imperial train, Nicholas II signed an act of abdication. In his diary on that day, the former emperor wrote: "Around treason, and cowardice, and deceit!"

In the text of the abdication, Nicholas wrote: "In the days of the great struggle with the external enemy, striving for almost three years to enslave our homeland. The Lord God was pleased to send down a new ordeal to Russia. The outbreak of internal popular unrest threaten to disastrously affect the further conduct of a stubborn war ... decisive days in the life of Russia We considered it our duty of conscience to facilitate the close unity and rallying of all the forces of the people for the speedy achievement of victory for our people, and in agreement with the State Duma, we recognized it for the good to renounce the Throne of the Russian State and resign from the Supreme Power ... "

Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich, under pressure from the Duma deputies, refused to accept the imperial crown. At 10 o'clock in the morning on March 3, the Provisional Committee of the Duma and members of the newly formed Provisional Government went to see Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich. The meeting took place in the apartment of Prince Putyatin on Millionnaya Street and dragged on until two in the afternoon. Of those present, only Foreign Minister P. N. Milyukov and Minister of War and Marine A. I. Guchkov persuaded Mikhail to accept the throne. Miliukov recalled that when, upon arrival in Petrograd, he "went straight to the railway workshops, announced the workers about Mikhail," he "barely escaped beatings or murder." Despite the rejection of the monarchy by the rebellious people, the leaders of the Cadets and Octobrists tried to persuade the Grand Duke to take the crown, seeing in Mikhail the guarantee of the continuity of power. The Grand Duke greeted Milyukov with a joking remark: "Well, it's good to be in the position of the English king. Very easy and convenient! Huh?" To which he quite seriously replied: "Yes, Your Highness, it is very calm to rule, observing the constitution." In his memoirs, Miliukov conveyed his speech to Mikhail in his memoirs: “I argued that strong power is needed to strengthen the new order and that it can be so only when it relies on the symbol of power, familiar to the masses. This symbol is the monarchy. the government, without relying on this symbol, simply will not live to see the opening of the Constituent Assembly. It will turn out to be a fragile boat that will drown in the ocean of popular unrest. The country is threatened with the loss of all consciousness of statehood and complete anarchy. "

However, Rodzianko, Kerensky, Shulgin and other members of the delegation had already realized that Mikhail would never be able to reign calmly like the British monarch, and that, given the excitement of the workers and soldiers, he would hardly be able to actually take power. Mikhail himself was convinced of this. His manifesto, prepared by a member of the Duma Vasily Alekseevich Maksakov and professors Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov (the father of the famous writer) and Boris Nolde, read: The supreme power, if such is the will of our great people, who must, through a popular vote through their representatives in the Constituent Assembly, establish the mode of government and new basic laws of the Russian State. " Interestingly, before the publication of the manifesto, a dispute arose that lasted for six hours. Its essence was as follows. The cadets Nabokov and Milyukov foaming at the mouth argued that Michael should be called emperor, since he seemed to have reigned for 24 hours before his abdication. They tried to maintain at least a weak clue for the possible restoration of the monarchy in the future. However, most of the members of the Provisional Government in the end came to the conclusion that Mikhail was, and remained, only the Grand Duke, since he refused to accept power.